When Daisy Christodoulou told us not to teach to the test, I assumed she was mainly concerned with teachers spending too much lesson time making sure children understood the intricacies of the mark scheme at the expense of the intricacies of the subject. Personally, I’ve never spent that much time on the intricacies of any mark scheme. I’ve been far too busy making sure children grasp the rudimentary basics of how tests work to have time spare for anything intricate. For example, how important it is to actually read the question. I spend whole lessons stressing ‘if the question says underline two words that mean the same as …., that means you underline TWO words. Not one word, not three words, not two phrases. TWO WORDS. Or if the questions says ‘tick the best answer’ then, and yes, I know this is tricky, the marker is looking to see if you can select the BEST answer from a selection which will have been deliberately chosen to include a couple that are half right. BUT NOT THE BEST. (I need to lie down in a darkened room just thinking about it).

When Daisy Christodoulou told us not to teach to the test, I assumed she was mainly concerned with teachers spending too much lesson time making sure children understood the intricacies of the mark scheme at the expense of the intricacies of the subject. Personally, I’ve never spent that much time on the intricacies of any mark scheme. I’ve been far too busy making sure children grasp the rudimentary basics of how tests work to have time spare for anything intricate. For example, how important it is to actually read the question. I spend whole lessons stressing ‘if the question says underline two words that mean the same as …., that means you underline TWO words. Not one word, not three words, not two phrases. TWO WORDS. Or if the questions says ‘tick the best answer’ then, and yes, I know this is tricky, the marker is looking to see if you can select the BEST answer from a selection which will have been deliberately chosen to include a couple that are half right. BUT NOT THE BEST. (I need to lie down in a darkened room just thinking about it).

But this is not Christodoulou’s primary concern.

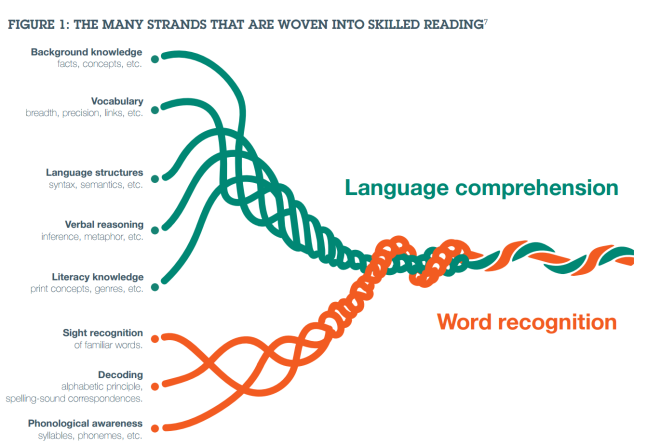

Christodoulou’s primary concern is that the way we test warps how we teach. While she is well aware that the English education system’s mania for holding us accountable distorts past and present assessment systems into uselessness, her over-riding concern is one of teaching methodology. She contrasts the direct teaching of generic skills (such as using inference for example) with a methodology that believes such skills are better taught indirectly through teaching a range of more basic constituent things first, and getting those solid. This approach, she argues, creates the fertile soil in which inferring (or problem solving or communicating or critical thinking or whatever) can thrive. It is a sort of ‘look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves’ or (to vary the metaphor) a ‘rising tide raises all boats’ methodology. Let me try to explain…

I did not come easily to driving. Even steering – surely the easiest part of the business – came to me slowly, after much deliberate practice in ‘not hitting anything.’ If my instructor had been in the business of sharing learning objectives she would surely have told me that ‘today we are learning to not hit anything.’

Luckily for the other inhabitants of Hackney, she scaffolded my learning by only letting me behind the wheel once we were safely on the deserted network of roads down by the old peanut factory. The car was also dual control, so she pretty much covered the whole gears and clutch business whilst I concentrated hard on not hitting anything. Occasionally she would lean across and yank the steering wheel too. However, thanks to her formative feedback (screams, yanks, the occasional extempore prayer), I eventually mastered both gears and not-hitting-anything. Only at that point did we actually go on any big roads or ‘ to play with the traffic’ as she put it. My instructor did not believe that the best way to get me to improve my driving was by driving. Daisy Christodoulou would approve.

Actually there was this book we were meant to complete at the end of each lesson. Michelle (my instructor) mostly ignored this, but occasionally she would write something – maybe the British School of Motoring does book looks – such as ‘improve clutch control,’ knowing full well the futility of this – if I actually knew how to control a clutch I bloody well would. She assessed that what I needed was lots and lots of safe practice of clutch control with nothing else to focus on. So most lessons (early on anyway) were spent well away from other traffic, trying to change gears without stalling, jumping or screeching, with in-the-moment verbal feedback guiding me. And slowly I got better. If Michelle had had to account for my progress towards passing my driving test, she would have been in trouble. Whole areas of the curriculum such as overtaking, turning right at a junction and keeping the correct distance between vehicles were not even attempted until after many months of lessons had taken place. Since we did not do (until right near the very end) mock versions of the driving test, she was not able to show her managers a nice linear graph showing what percentage of the test I had, and had not yet mastered. I would not have been ‘on track’. Did Michelle adapt my learning to fit in with these assessments? Of course not! She stuck with clutch control until I’d really got it and left ‘real driving’ to the future- even though this made it look like I was (literally) going nowhere, fast. Instead Michelle just kept on making sure I mastered all the basics and gradually added in other elements as she thought I was ready for them. In the end, with the exception of parallel parking, I could do everything just about well enough. I passed on my third occasion.

I hope this extended metaphor helps explain Christodoulou’s critique of teaching and assessment practices in England today. Christodoulou’s book ‘Making Good Progress?’ explores why it is that the assessment revolution failed to transform English education. After all, the approach was rooted in solid research and was embraced by both government and the profession. What could possibly go wrong?

One thing that went wrong, explains Christodoulou, is that instead of teachers ‘using evidence of student learning to adapt…teaching…to meet student needs’[1], teachers adapted their teaching to meet the needs of their (summative) assessments. Instead of assessment for learning we got learning for assessment.

Obviously assessments don’t actually have needs themselves. But the consumers of assessment – and I use the word advisedly – do. There exist among us voracious and insatiable accountability monsters, who need feeding at regular intervals with copious bucketfuls of freshly churned data. Imagine the British School of Motoring held pupil progress meetings with their instructors. Michelle might have felt vulnerable that her pupil was stuck at such an early stage and have looked at the driving curriculum and seen if there were some quick wins she could get ticked off before the next data drop. Preferably anything that doesn’t require you to drive smoothly in a straight line…signalling for example.

But this wasn’t even the main thing that went wrong. Or rather, something was already wrong, that no amount of AfL could put right. We were trying to teach skills like inference directly, when, in fact, these, so Christodoulou argues, are best learnt more indirectly by learning other things first. Instead of learning to read books by reading books, one should start with technical details like phonics. Instead of starting with maths problem solving, one should learn some basic number facts. Christodoulou describes how what is deliberately practised – the technical detail – may look very different from the final skill in its full glory. Phonics practice isn’t the same as reading a book. Learning dates off by heart is not the same as writing a history essay. Yet the former is necessary, if not sufficient basis for the latter. To use my driving metaphor, practising an emergency stop on a deserted road at 10mph when you know it’s coming is very, very different from actually having to screech to a stop from 40mph on a rainy day in real life, when a child runs out across the road. Yet the former helped you negotiate the latter.

The driving test has two main parts; technical control of the vehicle and behaviour in traffic (a.k.a. playing with the traffic). It is abundantly clear that to play with the traffic safely, the learner must have mastered a certain amount of technical control of the vehicle first. Imagine Michelle had adopted the generic driving skill approach and assumed these technical matters could be picked up en route, in the course of generally driving about, and assumed that I could negotiate left and right turns at the same time as maintaining control of the vehicle. When I repeatedly stall, because the concentration it take to both brake and steer distracts me from concentrating on changing gears to match this slower speed, Michelle tells me that I did not change down quickly enough, which I find incredibly frustrating because I know I’ve got a gears problems, and it is my gears problem I need help with. But what I don’t get with the generic skill approach is time to practice changing gears up and down as a discrete skill. That would be frowned on as being ‘decontextualised’. I might protest that I’d feel a lot safer doing a bit of decontextualized practice right now – but drill and practice is frowned upon – isn’t real driving after all – and in the actual test I am going to have to change gears and steer and brake all at the same time (and not hit anything) so better get used to it now.

Christodoulou argues that the direct teaching of generic skills leads to the kind of assessment practice that puts the cart, if not before the horse, then parallel with it. Under this approach, if you want the final fruit of a course of study to be an essay on the causes of the First World War, the route map to this end point will punctuated with ‘mini-me’ variations of this final goal; shorter versions of the essay perhaps. These shorter versions are then used by the teacher formatively, to give the learner feedback about the relative strengths and weaknesses of these preliminary attempts. All the learner then has to do, in theory, is marshal all this feedback together, address any shortcomings whilst retaining, and possibly augmenting, any strengths. However, this often leaves the learner none the wiser about precisely how to address their shortcomings. Advice to ‘be more systematic’ is only useful if you understand what being systematic means in practice, and if you already know that, you probably would have done so in the first place.[2]

It is the assessment of progress through interim assessments that strongly resemble the final exam that Christodoulou means by teaching to the test. Not because students shouldn’t know what format an exam is going to take and have a bit of practice on it towards the very end of a course of study. That’s not teaching to the test. Teaching to the test is working backwards from the final exam and then writing a curriculum punctuated by slightly reduced versions of that exam – and then teaching each set of lessons with the next test in mind. The teaching is shaped by the approaching test. This is learning for assessment. By contrast Christodoulou argues that we should just concentrate on teaching the curriculum and that there may be a whole range of other activities to assess how this learning is going that may look nothing like the final learning outcome. These, she contends, are much better suited to helping the learner actually improve their performance. For example, the teacher might teach the students what the key events were in the build up to the first World War, and then, by way of assessment, ask students to put these in correct chronological order on a time line. Feedback from this sort of assessment is very clear –if events are in the wrong order, the student needs to learn them in the correct order. The teacher teaches some small component that will form part of the final whole, and tests that discrete part. Testing to the teach, in other words, as opposed to teaching to the test.

There are obvious similarities with musicians learning scales and sports players doing specific drills – getting the fine details off pat before trying to orchestrate everything together. David Beckham apparently used to practice free kicks from all sorts of positions outside the penalty area, until he was able to hit the top corner of the goal with his eyes shut. This meant that in the fury and flurry of a real, live game, he was able to hit the target with satisfying frequency. In the same way, Christodoulou advocates spending more time teaching and assessing progress in acquiring decontextualized technical skills and less time on the contextualised ‘doing everything at once’, ‘playing with the traffic’ kind of tasks that closely resemble the final exam. Only when we do this, she argues, will assessment for learning be able to bear fruit. When the learning steps are small enough and comprehensible enough for the pupil to act on them, then and only then will afl be a lever for accelerating pupil progress.

Putting my primary practitioner hat on, applying this approach in some areas (for example reading) chimes with what we already do, but in others (I’m thinking writing here) the approach seems verging on the heretical. Maths deserves a whole blog to itself, so I’m going to leave that for now – whilst agreeing whole-heartedly that thorough knowledge of times tables and number bonds (not just to ten but within ten and within twenty – so including 3+5 and 8+5 for example) are absolutely crucial. Indeed I’d go so far as to say number bonds are even more important than times table knowledge, but harder to learn and rarely properly tested.  I’ve mentioned hit the button in a previous blog. We have now created a simple spreadsheet that logs each child’s score from year 2 to year 6 in the various categories for number bonds. Children start with make 10 and stay on this until they score 25 or more (which means 25 correct in 1 minute which I reckon equates to automatic recall. Then then proceed through the categories in turn – with missing numbers and make 100 with lower target scores of 15. Finally they skip the two decimals categories and go to the times table section – which has division facts as well as multiplication facts. Yes! When they’ve got those off pat, then they can return to do the decimals and the other categories. We’ve shared this, and the spreadsheet – with parents and some children are practising at home each night. With each game only taking one minute, it’s not hard to insist that your child plays say three rounds of this first, before relaxing. In class, the teachers test a group each day in class, using their set of 6 ipads. However since kindle fire’s were on sale for £34.99 recently, we’ve just bought 10 of them (the same as the cost of 1 i pad). We’ll use them for lots of other things too, of course – anything where all you really need is access to an internet browser.

I’ve mentioned hit the button in a previous blog. We have now created a simple spreadsheet that logs each child’s score from year 2 to year 6 in the various categories for number bonds. Children start with make 10 and stay on this until they score 25 or more (which means 25 correct in 1 minute which I reckon equates to automatic recall. Then then proceed through the categories in turn – with missing numbers and make 100 with lower target scores of 15. Finally they skip the two decimals categories and go to the times table section – which has division facts as well as multiplication facts. Yes! When they’ve got those off pat, then they can return to do the decimals and the other categories. We’ve shared this, and the spreadsheet – with parents and some children are practising at home each night. With each game only taking one minute, it’s not hard to insist that your child plays say three rounds of this first, before relaxing. In class, the teachers test a group each day in class, using their set of 6 ipads. However since kindle fire’s were on sale for £34.99 recently, we’ve just bought 10 of them (the same as the cost of 1 i pad). We’ll use them for lots of other things too, of course – anything where all you really need is access to an internet browser.

When we talk about mastery, people often talk about it like it’s this elusive higher plan that the clever kids might just attain in a state of mathematical or linguistic nirvana when really what it means is that every single child in your class – unless they have some really serious learning difficulty – has automatic recall of these basic number facts and (then later) their times tables. And can use full stops and capital letters correctly the first time they write something. And can spell every word on the year 3 and 4 word list (and year 1 & 2 as well of course). And read fluently – at least 140 words a minute, by the time they leave year 6. And have books they love to read – having read at least a million words for pleasure in the last year (We use accelerated reader to measure this – about half of year 6 are word millionaires already this year and a quarter have read over 2 million words.) How about primary schools holding themselves accountable to their secondary schools for delivering cohorts of children who have mastered all of these (with allowances for children who have not been long at the school or who have special needs) a bit like John Lewis is ‘Never Knowingly Undersold’, we should aim (among other things) to ensure at the very least, all our children who possibly could, have got these basics securely under their belt.

(My teacher husband and I now pause to have an argument about what should make it to the final list. Shouldn’t something about place value be included? Why just facts? Shouldn’t there be something about being able to use number bonds to do something? I’m talking about a minimum guarantee here – not specifying everything that should be in the primary curriculum. He obviously needs to read the book himself.)

Reading

My extended use of the metaphor of learning to drive to explain Christodoulou’s approach has one very obvious flaw. We usually teach classes of 30 children whereas driving lessons are normally conducted 1:1. It is all very well advocating spending as much time on the basics as is necessary before proceeding onto having to orchestrate several different skills all at the same time, but imagine the frustration the more able driver would have felt stuck in a class with me and my poor clutch control. They would want to be out there on the open roads, driving, not stuck behind me and my kangaroo petrol. Children arrive at our schools at various starting points. Some children pick up the sound-grapheme correspondences almost overnight; for others it takes years. I lent our phonics cards to a colleague to show here three-year-old over the weekend; by Monday he knew them all. Whereas another pupil, now in year 5, scored under 10 in both his ks1 phonic checks. I tried him again on it recently and he has finally passed. He is now just finishing turquoise books. In other words, he has just graduated from year 1 level reading, 4 years later. This despite daily 1:1 practice with a very skilled adult, reading from a decodable series he adores (Project X Code), as well as recently starting on the most decontextualized reading programme ever (Toe by Toe – which again he loves) and playing SWAP. He is making steady progress – which fills him with pride – but even if his secondary school carries on with the programme[3], at this rate he won’t really be a fluent reader until year 10. I keep on hoping a snowball effect will occur and the rate of progress will dramatically increase.

Outliers aside, there is a range of ability (or prior attainment if you prefer) in every class and for something as technical as phonics, this is most easily catered for by having children in small groups, depending on their present level. We use ReadWriteInc in the early years and ks1. Children are assessed individually by the reading leader for their technical ability to decode, segment and blend every half term and groups adjusted accordingly. So that part of our reading instruction is pretty Christodoulou-compliant, as I would have thought it is in most infant classes. But what about the juniors, or late year 2 – once the technical side is pretty sorted and teachers turn to teaching reading comprehension. Surely, if ever a test was created solely for the purposes of being able to measure something, it was the reading comprehension test, with the whole of ks2 reading curriculum one massive, time wasting exercise in teaching to the test?

I am well aware of the research critiquing the idea that there are some generic comprehension skills that can be taught in a way that can be learnt from specific texts and then applied across many texts, as Daniel Willingham explores here. Christodoulou quotes Willingham several times in her book and her critique of generic skills is obvioulsy influenced by his work. As Willingham explains, when we teach reading comprehension strategies we are actually teaching vocabulary, noticing understanding, and connecting ideas. (My emphasis). In order to connect ideas (which is what inference is), the reader needs to know enough about those ideas, to work out what hasn’t been said as well as what has been. Without specific knowledge, all the generic strategies in the world won’t help. As Willingham explains

‘Inferences matter because writers omit a good deal of what they mean. For example, take a simple sentence pair like this: “I can’t convince my boys that their beds aren’t trampolines. The building manager is pressuring us to move to the ground floor.” To understand this brief text the reader must infer that the jumping would be noisy for the downstairs neighbors, that the neighbors have complained about it, that the building manager is motivated to satisfy the neighbors, and that no one would hear the noise were the family living on the ground floor. So linking the first and second sentence is essential to meaning, but the writer has omitted the connective tissue on the assumption that the reader has the relevant knowledge about bed‐jumping and building managers. Absent that knowledge the reader might puzzle out the connection, but if that happens it will take time and mental effort.’

So what the non-comprehending reader needs is very specific knowledge (about what it’s like to live in a flat), not some generic skill. It could be argued then that schools therefore should spend more time teaching specific knowledge and less time elusive and non existant generic reading skills. However, Willingham concedes that the research shows that even so, teaching reading comprehension strategies does work. How can this be, he wonders? He likens the teaching of these skills as similar to giving someone vague instructions for assembling Ikea flat pack furniture.

‘Put stuff together. Every so often, stop, look at it, and evaluate how it is going. It may also help to think back on other pieces of furniture you’ve built before.

This is exactly the process we go through during shared reading. On top of our daily phonics lessons we have two short lessons a week of shared reading where the class teacher models being a reader using the eric approach. In other words, we have daily technical lessons, and twice a week we also have a bit of ‘playing with the traffic’ or more accurately, listening to the teacher playing with the traffic and talking about what they are doing as they do it. In our shared reading lessons, by thinking out loud about texts, the teacher makes it very explicit that texts are meant to be understood and enjoyed and not just for barking at and that therefore we should check as we go along that we are understanding what we are reading (or looking at). If we don’t understand something, we should stop and ask ourselves questions. It is where the teacher articulates that missing ‘connective tissue’, or ‘previous experience of building furniture’ to use Willingham’s Ikea metaphor, sharing new vocabulary and knowledge of the how the world works, knowledge that many of our inner city children do not have. (Although actually for this specific instance many of them would know about noisy neighbours, bouncing on beds and the perils of so doing whilst living in flats.)

For example, this picture (used in ‘eric’ link above) gives the the teacher the opportunity to share their knowledge that that sometimes the sea can get rough and that this means the waves get bigger and the wind blows strongly. Sometimes it might blow so hard that it could even blow your hat right off your head. As the waves rise and fall, the ship moves up and down and tilts first one way, and then the other. (Pictures are sometimes used for this rather than texts so working memory is relieved from the burden of decoding).

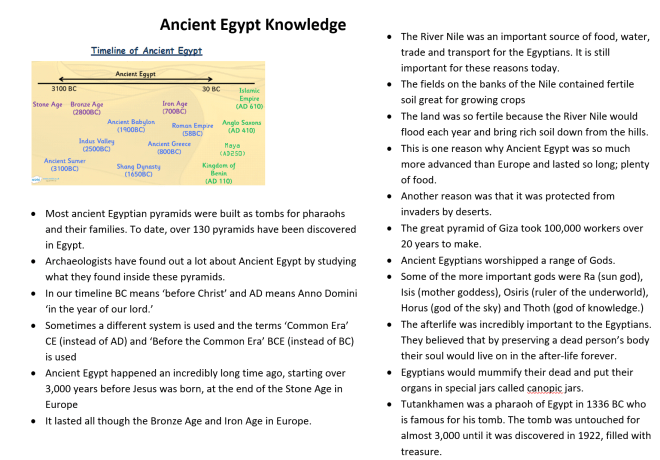

When teaching children knowledge is extolled as the next panacea, it’s not that I don’t agree, it’s just that I reckon people really underestimate quite how basic some of the knowledge we need to impart for our younger children. I know of primary schools proudly adopting a ‘knowledge curriculum’ and teaching two hours of history a week, with two years given over to learning about the Ancient Greeks. I just don’t see how this will help children understand texts about noisy neighbours, or about what the sea is like (although you could do that in the course of learning about Ancient Greece if you realised children didn’t know), or, for that matter, what it is like to mill around in bewilderment. The only kind of assessment that will help here is the teacher’s ‘ear to the ground’ minute by minute assessment – realising that -oh, some of them haven’t ever seen the sea, or been on a boat. They don’t know about waves or how windy it can be or how you rock up and down. This is the kind of knowledge that primary teachers in disadvantaged areas need to talk about all the time. And why we need to go on lots of trips too. But it is not something a test will pick up nor something you can measure progress gains in. The only way to increase vocabulary is one specific word at a time. It is also why we should never worry about whether something is ‘relevant’ to the children or not. If it is too relevant, then they already know about it – the more irrelevant the better.

I don’t entirely agree with the argument that since we can’t teach generic reading skills we should instead teach lots more geography and history since this will give children the necessary knowledge they need to understand what they read. We need to read and talk, talk talk about stories and their settings -not just what a mountain is but how it feels to climb a mountain or live on a mountain, how that affects your daily life, how you interact with your neighbours. We need to read more non fiction aloud, starting in the early years. We need to talk about emotions and body language and what the author is telling us by showing us. A quick google will show up writers body language ‘cheat sheets’. We need to reverse engineer these and explain that if the author has their character fidgetting with darting eyes, that probably means they are feeling nervous. Some drama probably wouldn’t go amiss either. Willingham’s trio of teaching vocabulary, noticing understanding, and connecting ideas is a really helpful way of primary teachers thinking about what they are doing when they teach reading comprehension. What we need to assess and feedback to children is how willing they to admit they don’t understand something, to ask what a word means, to realise they must be missing some connection. None of this is straightforwardly testable. That doesn’t mean it isn’t important.

Writing

Whereas most primary schools, to a greater or lesser degree, teach reading by at first teaching phonics, the teaching of writing is much more likely to be taught though students writing than it is through teaching a series of sub skills. It is the idea that we ensure technical prowess before we spend too much time on creative writing that most challenges the way we currently do things.

Of course we teach children to punctuate their sentences with capital letters and full stops right at the start of their writing development. However, patently, this instruction has limited effectiveness for many children. They might remember when they are at the initial stages and when they only write one sentence anyway – so not so hard to remember the final full stop in that case. Where it all goes wrong is once they start writing more than one sentence, further complicated when they start writing sentences with more than one clause. I’ve often thought we underestimate how conceptually difficult it is to understand what a sentence actually is. Learning to use speech punctuation is far easier than learning what is, and what is not, a sentence. Many times we send children back to put in their full stops, actually, they don’t really get where fulls tops really go. On my third session doing 1:1 tuition with a year 5 boy, he finally plucked up the courage to tell me that he know he should but he just didn’t get how you knew where sentences ended. So I abandoned what I’d planned and instead we learnt about sentences. I told him that sentences had a person or a thing doing something, and then after those two crucial bits we might get some extra information about where or why or with whom or whatever that belongs with the person/thing, so needs to be in the same sentence. We analysed various sentences, underlining the person/thing in one colour, the doing something word in another colour and finally the extra information (which could be adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, the object of the sentence – the predicate minus the verb basically) in another. This was some time ago before the renaissance of grammar teaching, so it never occurred to me to use the terms ‘subject’ ‘noun’ ‘verb’ etc but I would do now. It was all done of the hoof, but after three lessons he had got it, and even better, could apply it in his own writing.

What Christodoulou is advocating is that instead of waiting until things have got so bad they need 1:1 tuition to put it right, we systematically teach sentence punctuation (and other common problems such as verb subject agreement), giving greater priority to this than to creative writing. In other words, stop playing with the traffic before you’ve mastered sufficient technical skills to do so properly. This goes against normal primary practice, but I can see the sense in this. If ‘practice makes permanent’ as cognitive psychology tells us (see chapter 7 of What Every teacher Needs to Know About Psychology by Didau and Rose for more on this), then the last thing we want is for children to practice again and again doing something incorrectly. But this is precisely what our current practice does. Because most of the writing we ask children to do is creative writing, children who can’t punctuate their sentences get daily practice in doing it wrong. The same goes for letter formation and spelling of high frequency common exception words. Maybe instead we need to spend far more time in the infants and into year 3 if necessary on doing drills where we punctuate text without the added burden of composing as we go. Maybe this way, working memories would not become so overburdened with thinking about what to say that the necessary technicalities went out the window. After that, we could rewrite this correctly punctuated text in correctly formed handwriting. Some children have genuine handwriting or spelling problems and I wouldn’t want to condemn dyslexic and dyspraxic children to permanent technical practice. However if we did more technical practice in the infants – which would mean less time for writing composition – we might spot who had a genuine problem earlier and then put in place specific programmes to help them and/or aids to get round the problem another way. After all, not all drivers use manual transmission, some drive automatics.

Christodoulou mentions her experience of using the ‘Expressive Writing’ direct instruction programme, which I duly ordered. I have to say it evoked a visceral dislike in me; nasty cheap paper, crude line drawings, totally decontextualised, it’s everything my primary soul eschews (and it’s expensive to boot). However, the basic methodology is sound enough – and Christodoulou only mentions it because it is the ones she is familiar with. It is not like she’s giving it her imprimatur or anything. I’m loathed to give my teachers more work, but I don’t think it would be too hard to invent some exercises that are grounded in the context of something else children are learning; some sentences about Florence Nightingale or the Fire of London for example, or a punctuation-free excerpt from a well-loved story. Even if we only did a bit more of this and a bit less of writing compositions where we expect children to orchestrate many skills all at once, we should soon see gains also in children’s creative writing. Certainly, we should insist of mastery in these core writing skills by year 3, and where children still can’t punctuate a sentence, be totally ruthless in focusing on that until the problem is solved. And I don’t just mean that they can edit in their full stops after the fact, I mean they put them (or almost all of them in ) as they write. it needs to become an automatic process. Once it is automatic is it easy. Otherwise we are not doing them any favours in the long term as we are just making their error more and more permanent and harder and harder to undo.

Certainly pupil progress meetings would be different. Instead of discussing percentages and averages, the conversation would be very firmly about the teacher sharing the gaps in knowledge they had detected, the plans they had put in place to bridge those gaps, and progress to date in so doing, maybe courtesy of the ‘hit the button’ spreadsheet, some spelling tests, end of unit maths tests, records of increasing reading fluency. Already last July our end of year reports for parents shared with them which number facts, times tables and spellings (from the year word lists) their child did not yet know…with the strong suggestion that the child work on these over the summer! We are introducing ‘check it’ mini assessments so that we can check that we we taught three weeks ago is still retained. It’s easy, we just test to the teach.

[1] Christodoulou quoting D. Wiliams, p 19 Making Good Progress?

[2] Christodoulou quoting D. Wiliams, p 20 Making Good Progress?

[3] I say this because our local secondary school told me they didn’t believe in withdrawing children from class for interventions. Not even reading interventions. Surely he could miss MFL and learn to read in English first? As a minimum. Why not English lessons? I know he is ‘entitled’ to learn about Macbeth but at the expense of learning to read? Is Macbeth really that important? Maybe he will go to a different secondary school or they’ll change their policy.

When Daisy Christodoulou told us not to teach to the test, I assumed she was mainly concerned with teachers spending too much lesson time making sure children understood the intricacies of the mark scheme at the expense of the intricacies of the subject. Personally, I’ve never spent that much time on the intricacies of any mark scheme. I’ve been far too busy making sure children grasp the rudimentary basics of how tests work to have time spare for anything intricate. For example, how important it is to actually read the question. I spend whole lessons stressing ‘if the question says underline two words that mean the same as …., that means you underline TWO words. Not one word, not three words, not two phrases. TWO WORDS. Or if the questions says ‘tick the best answer’ then, and yes, I know this is tricky, the marker is looking to see if you can select the BEST answer from a selection which will have been deliberately chosen to include a couple that are half right. BUT NOT THE BEST. (I need to lie down in a darkened room just thinking about it).

When Daisy Christodoulou told us not to teach to the test, I assumed she was mainly concerned with teachers spending too much lesson time making sure children understood the intricacies of the mark scheme at the expense of the intricacies of the subject. Personally, I’ve never spent that much time on the intricacies of any mark scheme. I’ve been far too busy making sure children grasp the rudimentary basics of how tests work to have time spare for anything intricate. For example, how important it is to actually read the question. I spend whole lessons stressing ‘if the question says underline two words that mean the same as …., that means you underline TWO words. Not one word, not three words, not two phrases. TWO WORDS. Or if the questions says ‘tick the best answer’ then, and yes, I know this is tricky, the marker is looking to see if you can select the BEST answer from a selection which will have been deliberately chosen to include a couple that are half right. BUT NOT THE BEST. (I need to lie down in a darkened room just thinking about it). I’ve mentioned

I’ve mentioned