Talking floats on a sea of write

‘Writing floats on a sea of talk’ said James Britton in the 1970s.’ If you can’t say it, you can’t write it. This being the case, teaching children to write articulately will necessarily involve teaching children to speak articulately.

This is true but it is not the whole truth. Because the converse is also true; talking floats on a sea of ‘write.’ If you can’t write it, you can’t say it.

I can imagine you looking askance at his assertion and thinking, ‘Sealy’s lost it.’ After all, you are bound to know a four-year-old who doesn’t stop talking but can’t yet write very much. And for thousands of years there have been pre-literate cultures and civilisations that thrived without having any form of writing. Socrates refused to write because he thought it was a pernicious invention that would erode memory. Clearly Socrates could talk! So why the provocative assertion?

Britton’s assertion that teaching children to write articulately necessarily involves teaching children to speak articulately assumes that writing is transcribed speech. First a child learns how to talk then later they learn ways of transcribing that talk. However, because speech and writing are produced in very different communicative situations, there are significant differences in how they are structured. What is more, writing enables a different type of more formal speech. Exploratory talk and presentational talk, to use the categories first proposed by Douglas Barnes and then expanded upon by Neil Mercer, are different from every day, conversational talk. More formal ways of talking are dependent upon writing. If you can’t write it, you can’t say it. Or as Quintilian said in the first century, ‘By writing we speak with greater accuracy and by speaking we write with greater ease.’ Talking floats on a sea of ‘write.’

Clearly, the ability to participate in everyday conversation is not dependent on being able to write. But if we are talking about talking in an educational context, talking about the place of oracy in the curriculum for example, then we probably mainly mean something different from the sort of informal, conversational language we use every day. This is not to disparage the everyday vernacular, which is fundamental to our identity, to our sense of self. If we had to choose between only being able to communicate in the everyday vernacular or only being able to communicate in formal, sentence-based academic idiom, then the everyday would win, hands down. Humanity has existed for 300,000 years but has had written communication for only about 8,000 years. Mass literacy is a very new phenomenon, less than two hundred years old and far from universal even now. But there is a reason why mass literacy is seen as desirable. Becoming literate not only involves learning to read and write, it also involves learning to

In the same way that Michael Young talks about every day and powerful knowledge, we can distinguish between everyday vernacular and powerful disciplinary ways of talking. Some ways of powerful talking enable children to describe and elaborate, others to reason logically and yet others to empathise or imagine, to use the language functions outlined in the 70s by Joan Tough and revisited in Alex Bedford and Julie Sherrington’s EYFS: Language of learning. In the same way that Young’s powerful knowledge is specialised knowledge that gives students the ability to think about, and do things that otherwise they couldn’t, powerful talk is specialised talk that gives students the ability to talk about and hence think about things that otherwise they couldn’t. And these powerful ways of talking are inextricably linked to writing.

Differences between writing and speaking

There is one obvious difference between talking and writing that profoundly influences the nature of what each is able to communicate. Talk is transient, fleeting, ephemeral. Writing is durable; it has permanence. Spoken words appear and then disappear in the moment, vanishing without trace. Since working memory is fairly limited, the transience of speech means that it is challenging to articulate and organise complex thoughts or to revisit the complex thoughts of others. Speech is transient, ungraspable, intangible and therefore easily forgettable. The development of the technology of literacy extended working memory by outsourcing it to an external memory field – the written word – giving humans the ability to store and retrieve ideas efficiently and accurately.

Preliterate cultures had their own ways of hacking the limits of working memory. Through rituals, folktales, song, ballads, chants and poems, the transience of talk was captured and became memorable and transmissible via mnemonic tools such as repetitive and rhythmic language patterns. However, with nowhere[1] to store information outside of human minds, huge amounts of energy had to be devoted to keeping the oral culture alive. Socrates was opposed to writing because he could see that once culture could be stored externally, it would be evicted from the human mind.

The development of the technology of writing removed the limits on information storage and enabled information sharing across cultures and generations. As a result, human consciousness was now able to devote more energy to thinking about what was remembered rather than keeping the information alive. This shift from the wetware of the human brain to the hardware of tablet, scroll, page (or latterly – screen) enabled knowledge to be shared, contested, refined, elaborated and refuted.

The very fact that writing could store and enable retrieval of ideas resulted in a new type of communication related to, but different from the spoken word. Because everyday speech and writing are produced in very different communicative situations, there are differences in how they are structured. Both types of communication involve trade-offs. Because writing is durable and has permanence, unlike speech, it does not usually involve live interaction with a listener. This has the advantage that it is possible to communicate across time and space – through writing even the dead can communicate with us! Though this distancing also has drawbacks. Whereas with face-to-face speech, the speaker receives immediate feedback and can add in more details should their listeners appear confused, writers receive no immediate feedback from their readers. This places a responsibility on writers to explain things much more clearly and explicitly than when talking. Everyday conversation usually takes places between people who share a context. The speaker can make assumptions about what the listener already knows that a writer cannot. The potential for differences of culture or history between author and audience has structural implications for writing as a mode of communication. Vernacular ways of speaking work fine in a local, immediate context. But for written material that may be read by a reader at some remove in time or space from the author, standardised ways of writing need developing that mitigate linguistic differences.

Spoken language has its own drawbacks. It’s transient nature places burdens on the working memory not only of the speaker but of the listener. Spoken language therefore includes characteristics that are there to work around the limits of working memory and help the listener understand what is being spoken. For example, when speaking, we build in thinking time both for ourselves and our listener by using voiced hesitations such as ‘um’ and ‘ah’. We pause, repeat and rephrase so that listeners have time to absorb the spoken message and to give ourselves time to plan our next utterance. These hesitations are not only acceptable, they are necessary. The fixity of writing means these working memory workarounds are not necessary. The written word does not vanish once uttered. The reader can revisit written utterances. It is the reader who hesitates, who pauses, who rereads. Because writing is an asynchronous mode of communication, the reader can in effect ‘rewind’ the communication stream. The writer is expected to have already rephrased their thoughts into the clearest utterance possible prior to publication. Repetition, so necessary in spoken language, is frowned upon in writing. Writers deliberately try and use synonyms rather than repeat the same word within a sentence.

Speaking involves thinking on the spot. Writing gives you take up time to monitor and edit your thoughts. You can write a sentence, pause, reread it, reword it, change the order, extent it, abridge it or delete it. You have time to think about word choice, literacy devices, removing repetition, adding in rhetorical devices, changing sentence length. Writing can be polished in ways that conversational speech cannot. Writing is expected to be polished in ways that conversation speech is not.

To recap, writing needs to be clearer, more explicit, more standardised, less repetitive and more polished than spoken utterances. Writing therefore uses syntactical structures that are quite different from those used in conversation. Fragments abound in conversational speech. In writing, the sentence rules. The basic unit of spoken language is what is called a tone group, not the sentence. A tone group is a group of words said in a single breath and carrying a single thought. The permanence of writing permits more complex sentences, including those with subordinate clauses. Sentences frequently carry more than one thought, so need ways of indicating to the reader the boundary between one thought and another. In speech, tone of voice, timing, volume, stress and timbre in spoken communication communicate not only meaning but also attitude and emotion. These have no direct correlate in writing. Instead, punctuation plays a crucial though not entirely straightforward role in communicating meaning and emotional intent. Adverbs and adjectives are also much more common in writing, since emotion and intensity cannot be inferred from tone, stress or volume.

The profound structural differences between writing and everyday speaking mean that that learning to write is really complex. Learning to write isn’t just about learning to transcribe transient spoken utterances into permanent representations, it is about learning to communicate differently, using a very different syntax. When we learn to write, we are learning a new language, a language that is no one’s natal tongue. This language is what I’m a calling the language of ‘write.’ And it is a language we need to learn to speak not only in order to write – maybe AI will do much of that for us in the future – but in order to think the kind of complex, extended thoughts that writing makes possible. If you can’t write it, you can’t say it. So no, you don’t need to be able to write to be able to engage in everyday conversations. But learning to write is not just about actually writing. It is about learning an additional language, a language that allows the organisation and extensions of thought, a language that turbocharges the ability to think abstractly and analytically.[3] When we teach children to write, we are doing more than teaching them to represent their thoughts on paper. We are teaching them new ways of thinking. As Gunther Kress has written, it involves ‘learning new forms of syntactical and textural structure, new genre, and new ways of relating to unknown addressees’.[4] These new ways will be used not only when writing, but when discussing ideas in class. This is why it is important to help children develop the ability to discuss ideas using full sentences. Sometimes this is criticised on the grounds that we do not use full sentences in everyday conversation. This misses the point. Learning to discuss in class is learning to express oneself using this new language, because this language is better suited to abstract and analytic thought than the vernacular. This is not to disparage the vernacular. It’s not inferior. It is just different and has different strengths. Vernacular, everyday speech is at the heart of being human. It is central to identity. It should be respected and cherished. But if we believe that all our children belong in academic spaces, then we need to empower them to speak the powerful language of ‘write’.[5]

In everyday speech, we use words like ‘right’, ‘so’, ‘well’ or ‘anyway’ ‘I mean’ ‘mind you’ ‘look’ as discourse markers to connect and organise our thoughts. When writing, we use different discourse markers: ‘first’ ‘in addition’ ‘moreover, ‘to begin with’ ‘on the one hand.’ Since spoken communication takes place in a social context, spoken rituals to establish and maintain relationships bookend interactions. Known as phatic communication, examples include ‘How are you?’ or ‘You’re welcome,’ or talking about the weather. Such phatic communication is present in written communication of a social nature – in emails or letters for example. But since writing chiefly exists to enable communication without social interaction, phatic communication is redundant in most writing events.

This language of ‘write’ can be spoken as well as written. If you are listening to a speech or a documentary or a talk at an educational conference, you are probably listening to the language of ‘write’. But at some point, maybe many years ago, this oral event was written before it was spoken. There’s script or an article, or a blog or a book or a plan behind the spoken event. People just don’t talk at length in extended and coherently joined sentences without either having written it down first or having read and remembered the writing of someone else. Probably both. Our working memories are too small to enable us to talk in extended prose for long periods. Or at least, to talk well. Spontaneous, conversational speech uses vernacular forms of expression; prepared and planned speaking usually uses the language of ‘write.’ And of course, it is possible to write using the vernacular, particularly when the writing has a social purpose – a text message, an email, a letter, for example.

Having begun as a way of communicating at a distance, formal academic writing adopts language structures that assert this detachment through removing the grammar of the personal. Far from perceiving the absence of social interaction as weakness, formal academic writing sees its deliberate impersonal stance as underpinning objectivity. The focus is on what is written rather than the writer. Academic thought is – or at least should be – an ongoing truth quest untrammelled by group loyalty or personal circumstance.[2] It therefore explicitly rejects tell-tale signs of social interaction, codifying detachment from the sphere of social influence by such devices as writing in the third person, using passive voice constructions and nominalised forms of verbs (invasion rather than invade, decision rather than decide) deliberately impersonal. Modal verbs convey the provisional, tentative and challengeable nature of written thought.

Implications for teaching writing

When people talk about the importance of oracy in the curriculum, different people mean different things. Some people mean by this that there should be more place for spontaneous, informal, interactive talk. Others that we should give children the tools to be able to present their ideas orally to audiences. Some people think that oral presentations should have more prominence than written work in the mistaken belief that because speaking is natural whereas writing has to be explicitly taught, allowing children to express themselves orally is easier and fairer. But when we ask children to articulate academic ideas, they need to be able to do so using academic syntax – the language of ‘write’. This is not easier orally. In fact, its harder. It’s expecting people to use complex language structures developed for communication expressed in durable and easily revisable form, in a spontaneous, unplanned manner, using a different language from that learnt in the home. No wonder many people find this kind of more formal speaking anxiety-inducing. Indeed, some people even prefer text message to phoning, partly because writing gives you time to think and space to revise your thoughts.

The oracy skills framework – maybe better named as James Mannion says as the oracy knowledge and skills framework – goes some way to helping here. It describes four different dimensions of oracy: physical, linguistic, cognitive and social and emotional and describes some of the forms of knowledge each dimension necessarily includes. I think it is quite a useful starting point to think about oracy in curricular terms. (Mannion’s distinction between learning to talk and learning through talk in the above blog is also useful). However, like many graphics representing different aspects within a curriculum, by having similar sized boxes, it is open to the misinterpretation that size of the box indicates relative important. So if all the boxes are the same size, then all of these elements are equally important and demand equivalent curricular time. Whereas, since learning to speak the language of ‘write’ is akin to learning another language, the language aspects within the linguistic box is far more important and should take up much more time than many of the others. And by separating out oracy as a curricular thing, separate from writing, obscures the dependence of one with the other. Talk – or at least academic talk – floats on a sea of writing. Learning about this interdependence is useful. Learning that why trying to talk ‘write’ is particularly challenging (given you are attempting to speak spontaneously in the medium designed for asynchronous communication) might be helpful.

When using exploratory talk in class, it may be appropriate to use vernacular spoken forms. Written idiom is too clunky for spontaneous, social interaction, and plain weird used within conversations. Exploring ideas with others in the moment means participants need the thinking time that voiced hesitations and repetitions provide. The choice of register is dependent on the communicative function. However, we may also want to help children take their spontaneous utterances and translate them into the more formal, more explicit, language of ‘write’, not because spontaneous language is inferior but because it is less suited to the extended thought of academic discourse. So this may involve spontaneous utterance, commitment of spoken utterance on paper or white board, and then recasting of that utterance into written idiom. Once written in durable, revisable form, the utterance may then be spoken to an audience in a more formal way.

(One reason children like white boards is because they act as an ‘no man’s land’ between transient speaking and formally phrased sentence. It enables fleeting phrases to be captured, revised and recast into sentenced-based written idiom, and then – and I think it is this bit that is particularly appreciated – the evidence of that revision is erased.)

Learning to use the grammar and register of academic writing – whether writing or speaking, is going to take a lot of investment. Children arrive in school speaking in tone groups, not sentences. No wonder so many children write in fragments. There is so much more to understanding and using sentence constructions than full stops and capital letters. In order to learn the language of ‘write’, children will need repeated exposure to the language patterns of writing through exposure to high quality children’s literature and copious amounts of non-fiction. Learning through talk, though valuable, is not by itself going to be enough to enable children develop the syntax of the language of ‘write.’ That comes through hearing an adult read to you. Decodable texts are vital for learning to lift words of the page. They are not going to teach model the language patterns of writing – they are not intended to.

Alongside immersion in the language of ‘write’, children also need opportunities to focus in on its syntactical structures. If learning the language of ‘write’ has similarities with learning a new language, then it is useful to explore what might be learnt from language teachers. In particular, from the ‘extensive processing instruction’ or EPI approach articulate by Gianfranco Conti and others. Clearly since learning to communicate in the idiom of written English is not exactly like learning to communicate in French, not every element applies.

The EPI approach provides learners with chunks of communicatively useful, highly patterned language and repeats these again and again, making tiny changes as the same structure is applied in minimally different contexts. Children are ‘flooded’ with simplified, repetitive, highly patterned, tightly controlled chunks of language. Unlike previous approaches to teaching modern foreign languages, there is little emphasis for beginners on encountering authentic texts. The curriculum structure provides a scaffold to enable success. Language structures are at first modelled, then reading and listening activities are provided that enable receptive processing, then highly structured opportunities to produce language in writing and orally. Only once all of this has been done to a point where all children are able to be successful are learners expected to use what they have learned autonomously and creatively. Competence in receptive language – reading and listening – come before expecting competence in productive language – writing and speaking.

This ‘receptive before productive’ journey is useful thinking about how we might teach children the language of ‘write’. The reading curriculum in primary schools, and through embedding the reading of texts in subjects in the secondary curriculum (where this is disciplinarily appropriate), we can expose children to unfamiliar language structures of the language of ‘write.’ Then we can use sentence frames and sentence builders to provide highly structured opportunities for writing and speaking. Instead of rushing headlong into expecting children to produce unstructured extended writing or talking, the curriculum deliberately scaffolds learning. The early emphasis on extended writing in primary schools is misplaced. Being expected to use writing or speech to communicate extended though, when children are still novices in learning the syntax of this new language sets many up for failure.

It is not just syntax that early writers need to learn. The transcriptional elements of both handwriting and encoding sounds into words in spelling, both need – separately – to receive prime curriculum time alongside highly structured and short writing opportunities based on extensively modelled, communicatively useful language structures.

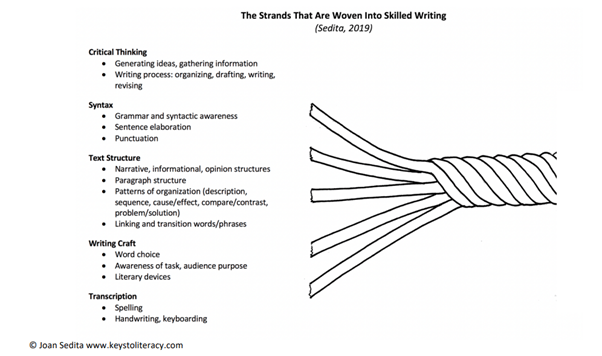

Like reading, writing is a multi-component process. Scarborough’s reading rope graphic depicts the multiple components of reading as strands in a rope. As students develop skills in these components, they become increasingly strategic and automatic in their application, leading to fluent reading comprehension. Joan Sedita proposes that a similar “rope” metaphor can be used to depict the many strands that contribute to fluent, skilled writing, as shown in the graphic below.

I think this graphic is useful. However, like the oracy framework graphic, it could potentially mislead insofar as it could lead people to think that learning about all strands is equally important at every phase of learning. However, for novice learners, there are two key strands, the transcription strand (though I’d prefer this strand to be further split into two different strands since they need to be learnt separately[6]) and the syntax strand. The text structure and writing craft strands are developed through receptive language activities – through the reading curriculum rather than through the writing curriculum. Many primary schools expect children to write at length long before they have the tools necessary to do so well. Not only does this undermine their ability to write, it also interferes with their ability to learn to use the language structures of writing that underpin much analytical and abstract thinking. While children should encounter a wide range of genres in their reading, it is counterproductive to teach them to write a wide variety of genres. Alongside learning how to spell and produce legible handwriting, children need explicit and systematic teaching about what it means to craft written sentences.

Andy Percival, deputy headteacher at Stanley Road Primary in Oldham, has developed a sentence knowledge curriculum, adapted from Step Academy Trust and available on completemaths.com. See here for the structured activities that help children internalise these structures. Andy has described how the emphasis on the different strands integral to learning to write might change from the Early Years Foundation Stage to year 6. VGP stands for vocabulary, grammar and punctuation and is where much of the sentence knowledge curriculum is taught. Comp stands for comprehension.

This writing curriculum is complemented by a reading curriculum that exposes children to high quality models of children’s literature and opportunities for oral development. Rather than expect children to write at length in ks1, composition opportunities could include the oral retelling of stories, possibly using story maps to scaffold memory of the plot (as in a Talk for Writing approach).

Another strategy for scaffolding sentence development – the of Slow Writing – is described here by David Didau, this time in a secondary school context. David write that not only does this make students better at writing, it makes them better at thinking.

I rest my case.

[2] I’m not saying it always achieves this, but that is its aim.

[3] Some caution is need here. Anthropologists have demonstrated that abstraction and analysis is not the sole preserve of western literate societies. There is, for example, scientific thinking and non-scientific thinking within all societies. However, the invention of writing not only enabled cross cultural and cross generation sharing of ideas, but also strengthened the belief that striving after the truth was an ethical endeavour

[4] Gunter Kress, Language of Writing, Routledge, 1993

[5] This phrase comes from Zaretta Hammond. Thanks to Sonia Thompson for introducing me to it.

[6] Indeed, handwriting itself is a multicomponent process involving four different strands.