It’s now official, with the election of a Labour government in the UK, oracy is now the Next Big Thing about to preoccupy schools in England. (England rather than the UK as a whole, because authority for education is devolved to each of the four nations in the United Kingdom, so this is about England rather than Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales) This is not a bad thing at all, except in the way that all Next Big Things can be bad things in that schools often rush to adopt superficial aspects rather than engaging deeply with the underlying rationale in a way that genuinely makes things better. Many schools have a regrettable tendency to prioritise observable and auditable actions over fostering deep understanding of strategies introduced with the best of intentions. In what follows, I will attempt to set out how we might think about oracy in ways that strengthen our educational offer as well as highlighting ways in which these might be mutated into unhelpful ends.

Oracy is a curricular as well as pedagogical concern

James Mannion, one of the authors of the Oracy Skills Framework, writes that oracy is more than learning through talk. Children also need to be taught how to talk. Indeed James writes that perhaps it would have been better to call the oracy skills framework the oracy skills and knowledge framework and that ‘there is a significant body of knowledge that underpins the development of spoken language and communication,’[1]. Oracy is both a curricular and a pedagogical concern. Intelligent thinking about oracy therefore need to reflect upon the roles (plural) of speaking and of listening in pedagogy and its roles in the various subject curricula. Oracy is not a ‘thing’ that we do in a performative ‘look-at-us-doing-oracy’ dance, it is a range of teaching practices, whole school routines and subject specific curricular objects. Hence oracies not oracy.

There are broadly three main reasons why oracy is advocated. The first is around self-confidence. Education, it is argued, should enable children to develop into self-confident individuals who can communicate with ease in a range of social situations, beyond the narrow confines of their peer group. Children should feel able to express their ideas, ask questions, voice opinions, engage in conversation with an unfamiliar person or group of people and do all of these constructively and effectively with the requisite politeness the situation demands.

The second reason is about teamwork and collaboration. Education should enable children to work with others to achieve goals. For this to happen children need to be able to participate in a discussion as an equal partner, listening attentively, building on the contributions of others and disagreeing amicably when appropriate. It is about balancing one’s own self-confidence with the right of other voices to be heard. We might note, in passing, that at least in part, the first of these is about encouraging the more reticent to speak, the second is about reminding the more loquacious to listen!

These first two reasons have both pedagogical and curricular implications. Having regular opportunities to learn through talk, whether through routines such as talk partners, or group work or whole class discussion, provide contexts within which speaking and listening can be applied. However, students also need to learn how to talk and how to listen. When explicit teaching about this is omitted, and children just left to get on with it, this is very likely to go wrong. As the oracy skills [and knowledge] framework reminds us, there are four major strands of learning to speak and listen well; the physical, the social emotional, the linguistic and the cognitive. While the linguistic and cognitive may be included within subject teaching, the physical and social emotional may well be overlooked, or assumed to be ‘natural’ so not in need of explicit teaching. In the same way that schools should have a behaviour curriculum that teaches children the detail of how to behave in a pro-social, pro-learning manner, schools should also explicitly teach the physical and social emotional granular detail of how to speak and listen well. One reason this may be overlooked is that outside of the Foundation Stage, it does not have an identified curricular ‘home’, though the English, drama and PHSE curricula all provide natural contexts for explicit teaching about how to speak and listen. This learning can then be consolidated and applied across the curriculum, when appropriate in pedagogical and curriculum terms. Explicit structures and expectations such as outlined in accountable talk or habits of discussion, can scaffold and reinforce this prior learning.

The third reason is around learning effectively. There is substantial evidence that oral language competence underpins cognitive development; talking and thinking being intimately entwinned. [2] Below, oracy as pedagogy expands upon how oracy can be deployed pedagogically to strengthen learning by enabling checking for understanding, developing fluency in the language of analytic thought and by causing children to think hard and think with taught content.

A fourth seldom expressed reason is that to different degrees depending on the subject, the omission of learning how to communicate orally does violence to the essence of that subject. Drama without speaking and listening is unthinkable, learning a modern foreign language without learning how speak it and understand its spoken form is an emaciated form of language learning. The study of English is seriously impoverished unless it includes study of the spoken word as well as the written word. The extent to which the internal logic of other subjects should include curricular objects concerning speaking and listening is discussed later. This is separate from discussion of the use of oracy as pedagogy. Muddled thinking about whether oracy is being used for curricular or pedagogical reasons is a sure sign that things are about to go very wrong. The section on oracy as curriculum expands upon this.

Oracy as pedagogy

Teachers have a range of pedagogical tools at their disposal and are faced with the professional challenge of making judicious choices about which tools are best suited to which tasks, subjects and age of pupil and at which point in a lesson.[3] There is an opportunity cost to any decision. To choose to use speaking means there is less time to apply writing or digital skills for example, and in a given situation writing or a digital technological tool might be a more effective choice for learning something than the alternatives. The rationale behind such decisions is not often articulated and yet being able to weight and justify one’s pedagogical choices is the best insurance against their misapplication. Given that oracy is often advocated in the belief that getting pupils to justify their assertions is an inherent good, then we should expect proponents of oracy to be eloquent at justifying their pedagogical choices.

Building belonging

There are a raft of reasons for using oracy as a pedagogical tool. First of all, the use of oracy in the classroom can be done in such a way as to build a sense of belonging and of shared purpose in a way that is superior to using alternatives such as writing or digital technology. Which is not to say that neither writing nor digital technology cannot also be used in the service of building belonging – for example online writing collaboration tools allow these two to be used in combination. However, oracy has a particularly strong contribution in building belonging. After all, we use expressions such as ‘having a voice’ and ‘being heard’ as crucial aspects of being respected as a person. The language we speak is a central part of our sense of identity. Therefore, being listened to, having one’s voice respected and valued should be a fundamental part of every school’s ethos. The oracy benchmarks of Voice 21 has as its second benchmark the valuing of every voice.

‘ The teacher supports all students to participate in, and benefit from, oracy in the classroom. The teacher listens meaningfully to students, encouraging them to develop their ideas further, and creates a culture in which students do the same.’

Doug Lemov in his book Reconnect for Meaning, Purpose and Belonging writes about teaching that amplifies the signals of belonging. He discusses pedagogical routines such as turn and talk and habits of discussion as ways of building a sense of belonging, valuing every child’s voice and providing a context for children to learn to expand upon and justify their reasoning. A classroom with the emotional safety that enables every child to share their voice is a classroom where is it safe to take risks and make mistakes.

Clearly, building belonging is important in its own right. There is however a further contribution that a sense of belonging provides – though it sounds a little instrumentalist if not outlined without first stressing its non-instrumental moral necessity. Feeling you belong is one aspect of what drives motivation and teaching is much more effective – and rewarding – with motivated learners than with unmotivated learners.

Checking for understanding

A second reason why a teacher might make a decision to use oracy as a pedagogical choice is in order to check for understanding. Learning is invisible so teachers rely on proxies in order to try and work out if their teaching is having the desired learning outcome. There are three main ways teachers could check for understanding; children could write their answers, possibly on a mini whiteboard, children could choose an option either on a digital device or by using a physical signal, moving to a certain place, showing a coloured car or number of fingers or whatever, or by talking – to a partner or to the class as a whole. All of these have their merits and drawbacks.

Choosing options is only suitable for simple yes/no, true/false or multiple-choice questions, but because it is an all-learner response system, (as opposed to asking for ‘hands up who knows the answer routines’), it gives the teacher instant data on the extent of understanding across the class as a whole. This is powerful data which empowers the teacher to flex their teaching in the moment to address misconceptions.

Writing on a mini white board or quizzing technology such as Carousel allows for slightly longer answers and still provides the opportunity for the teacher to check for understanding. The challenge of so doing increases with the length of the answer, so there is a law of diminishing returns here once answers become longer than a simple sentence.

Similarly, using talk partners allows for both short and slightly longer answers and provides a context for teachers to sample understanding across the class if used alongside all learner response systems such a cold calling (done warmly, naturally).

This may make it sound as if checking for understanding involves questions with simple, closed answers is in some way inferior to asking a question that involves a longer, more open answer. This is not the case. Closed questions play a vital role in checking and reinforcing key knowledge and in building confidence with subject content, both of which underpin a learner’s ability to answer a more open-ended question.

It is usually easier to check for understanding when asking an open-ended question by using spoken answers as a means of participation than the above alternatives. However, as there usually are with pedagogical decisions, there is a trade-off to be made. Put simply, a teacher can either attend to one learner giving a longer answer or many learners giving short written or signalled answers. Both have their place, depending on whether the teacher wants to know whether everybody understands or whether child X specifically understands. (There are of course reasons other than checking for understanding for engaging in extended, probing verbal exchanges with one child.)

In practice, teachers manage these different trade-offs by using techniques in combination. For example, an all-learner response system such as using mini white boards or a multiple-choice quiz is used and then the teacher selects a child to answer verbally. Another strategy is using what Adam Boxer calls ‘indicator’ children, those children who the teacher is aware are more likely to find learning more challenging and use these children as a way of sampling understanding more generally.

Proponents of dialogic teaching such as Robin Alexander, for example, are dismissive of checking for understanding routines, or what they call IRF (Initiation by the teacher; Response by a student of students; Feedback from the teacher). Checking for understanding is disparaged as ‘reporting on someone else’s thinking rather than think[ing] for themselves.’[4] However, checking for understanding is a vital tool in an inclusive classroom and has a specific rationale: that of providing the teacher with information about whether they need to clarify or give more practice to an area of learning. The idea that ‘thinking for themselves’ is possible without deep immersion in ‘someone else’s thinking’ is somewhat fanciful and seems to dismiss the foundational role of knowledge in thinking. Unless we are expecting each and every child to rediscover the cumulative legacy of human meaning making afresh then learning other people’s thinking is here to stay. Be very wary of those who are dismissive of the power and necessity of oral checking for understanding routines and who are overly enthusiastic about open-ended, exploratory discussion to the exclusion of anything else. Open-ended exploratory talk is important both pedagogically and in terms of the curriculum in some subjects, but it is not the only thing that is important.

Speaking: writing co–dependencies

A third pedagogical reason for using oracy is to enable learners to reframe and extend their initial thoughts into a more formal speech mode. Formal speech has structural and lexical differences with conversational speech and is inextricably linked with writing. I have written about this in detail in this blog which I really urge you to read in order to fully understand the co-dependency that exists between speaking and writing.

The formal mode is the communication mode that is optimised for analytical thought. It uses sentence-based idiom and technical vocabulary and is more polished – more formal – than its conversational progenitor. Sometimes such language is described as being ‘higher quality’ or ‘better.’ [5] But these adjectives are context specific – a more formal full sentence is better in some contexts and inappropriate in others. In the classroom, there will be many occasions when we wants students to recast their initial, fleeting thoughts into something more polished, more considered and more analytical. Here, exploratory talk gives space for the learner to reflect upon and recast their initial thoughts into something more organised. It gives space for thought to be listened to by others, questioned, and developed further.

Academic language – whether written or spoken – is written in sentences. Conversational language is not. Exploratory talk in the classroom provides a way of bouncing between the two. Respect the role of both in communication. Be wary of approaches that either insist that children speak in full sentences all the time, or who conversely do not appreciate the need to be able to talk in full sentences when it is appropriate to do so.

Being able to communicate in sentence-based idiom is no one’s natal tongue. Learning to do so requires thoughtful scaffolding as well as many, many opportunities to practice. Just giving curriculum time to children talking together without scaffolding is not going to enable them to learn how to communicate in this new idiom. To paraphrase James Britton’s oft cited , ‘sentence-based writing floats on a sea of sentence-based talk!’ If you can’t say it in full sentences, you can’t write it in full sentences. The fact that in conversation we do not speak in full sentences is a complete red herring. There is a valuable place for exploration of ideas in the classroom that does not insist in full sentences and there is also a perhaps even more valuable role for learning to articulate ideas in formal academic mode. There is also a curricular dimension to articulating thought in more formal idiom because not only the vocabulary but also the grammar choices are deeply shaped by the subject within which one is communicating. This is examined below.

(I urge you once again to read this blog where I expand upon this in more detail.)

Thinking hard

A fourth, closely allied pedagogical reason for using talk in the classroom is that it has the potential, done well, to enable learners to think hard – or think with – the content that has been shared with them. It also has the potential to enable learners to avoid thinking hard, particularly because the transient nature of a class full of students all taking at once provides is hard for teachers to monitor whether or not this hard thinking is actually taking place. Unless a teacher is skilled in pre-emptive strategies to address this, a class full of talking students provides easy cover for students seeking to avoid the hard work of thinking. Such pre-emptive strategies for creating an ethos for productive talk exist and need to be understood, modelled and practised if the use of talk is going to be pedagogically productive. For example,

‘Accountable Talk practices are not something that spring spontaneously from students’ mouths. It takes time and effort to create an Accountable Talk classroom environment in which this kind of talk is a valued norm. It requires teachers to guide and scaffold student participation.’[6]

These caveats aside, talk between peers has the potential to get students thinking hard about content. When students think with content – having to mentally translate it from one context to another – in this case from the teacher’s words into their own words and the words of their peers, this involves the kind of effortful thinking likely to lead to effective learning.

Using talk as a way of getting students to think hard – and think with – content, using talk, can also be structured through skilled extended probing, sometimes of just one student, with other students attentively listening – and benefitting – from the exchange. For some, this is the oracy motherlode.

The advocacy oracy providing the means for children to ‘think for themselves’ warrants some unpicking because there is often a conflation between two different concepts occurring when it is championed. There is a first sense in which it means something like ‘make sense of what you have just learnt by integrating it within your preexisting mental schema, making new links.’ It involves the learner engaging in cognitive activity – what I have called thinking with new content above, in order to make sense of it. Generative learning strategies, as researched by Fiorella and Meyer, are ways of enabling such thinking and often either involve talk or have the potentially to be done in pairs or small groups using talk.

The second sense is more about having your own opinion about something, making decisions whether to accept or reject a proposal, justifying one’s line of reasoning and so on. However, such considerations take us deep into curricular territory. Voicing opinions, for example, forms a larger part of the cognitive architecture of some subjects than others and so the amount of time deployed should vary accordingly. Voicing one’s opinion of the meaning of a poem is an integral part of the English curriculum; voicing one’s opinion about whether or not F=ma is not part of what it is to learn physics.

At this point you may be thinking, but what about the value of exploring ideas with peers per se – quite apart from the role of talk in either cementing learning or learning how to express oneself in academic idiom. What about a space for provisionally, for turning over ideas and opinions? For this, we need to explore oracy within the curriculum as reasoning, explanation and opinion giving are not generic abilities. They are shaped by the subject within which they are taking place.

Oracy as curriculum

That most schools in England now embrace the idea that having a coherent curriculum is a necessary if not sufficient component of a good education is a major achievement. However, there is more to understanding curriculum than appreciation that knowledge is important and should be sequenced in a way that reinforces and deepens prior learning while making connections to and preparing for new learning. An aspect of curricular understanding that is less well developed is that concerning how the different subjects are different and the implications those differences have for how and what we teach.

More often we hear concerns about ‘teaching subjects in silos’ without understanding that knowledge is structured differently in different subjects for good reasons which makes a degree of containment – or siloing if you will – not only inevitable but important. Each discipline is a search for meaning, a particular truth quest. As Ruth Ashby explains in her excellent book Curriculum: Theory, Culture and the Subject specialisms ‘a discipline’s practitioners look out at the word in unique ways; they notice certain types of things, they ask certain types of question…’ If we try and blur the distinctiveness of the different disciplines, we lose specific ways of noticing and narrow the range of ways in which we can make meaning. As Ruth describes, we can describe these quests after meaning as fitting into four different categories; descriptive, interpretative, expressive and problem solving.

Some disciplines describe the world, seeking to ‘find facts and to make meaning from then; to distil, interpret, reduce or generalise.’ Science and maths in particular, and some aspects of geography, history and religious studies follow descriptive quests, using logic and empiricism in the service of truth seeking. Objectivity is assumed to be both possible and desirable.

Some subjects interpret the world. In interpretive quests, subjective interpretation is valued, truth being sought through reasoned argumentation. Much of history, theological aspects of religious studies, literacy criticism, art and some aspects of geography ‘all have explicit interpretive aspects to their quests, and do not seek objectivity or single-truth in the way that science and mathematics do.’

Yet other subject quests are expressive – for example the arts – and seek approval not just from the subject community but also from curators, critics and the interested public. This is very different from truth-seeking grounded in empirical testing as used by the sciences. Finally we have the problem seeking quest followed by design, computing engineering, food technology and so on.

It is important to notice that a single subject may straddle more than one ‘quest.’ History, for example, is both descriptive and interpretive. English is by turns descriptive (for example, in phonics), interpretive (for example when seeking to understand a text) and expressive (for example when writing or voicing a personal response to a poem).

In a broad and balanced curriculum, children learn to make meaning in all these different ways. Part of the curriculum in a subject in learning how meaning is made, how knowledge is accepted, contested or refuted. Subjects with interpretive and expressive quests require space in which the ability of children to engage with and in interpretation and expression in a way that descriptive and problem-solving subjects do not.

Even within interpretive subjects, while diversity of thought and subjective opinion is integral to the subject, that does not mean that all opinions are equally valid and that there are no wrong answers. Opinions are not just aired; they are justified with respect to evidence. One way in which oracy can go very, very wrong is in the wrong-headed belief that expressing opinions is good in itself, regardless of what knowledge may tell us and without the expectation of rigorous thinking. A notorious example of this occurred on Twitter, when a prominent headteacher championed children voicing doubts about the moon landings because he appeared to value having an opinion and challenging accepted narratives over having due regard for evidence. This is to promote a conspiracy theory curriculum which should have no place in any school.

The University of Pittsburgh promotes a practice called Accountable Talk. Children -and one would hope their headteachers – are accountable ‘to the learning community, to accurate and appropriate knowledge, and to rigorous thinking.’

They write about how talk is used in different subjects here.

‘Disciplines vary in the types of evidence they value. When students are digging into a good poem or story, for instance, they might be trying to sense how the words and rhythms create tension or convey emotions. No one expects a student to provide a “proof” for her claim that a verse evoked a particular emotional response. However, if a student provides an interpretation of the motivation behind a character’s actions, we expect that student to cite multiple pieces of textual evidence to support that interpretation. Within a social studies lesson, students may marshal historical facts to support a position that begins as an “opinion.” But if a student explaining his thinking about a fractions problem were to say, “I think the 4 stays the same because it just feels right that way,” he is not being accountable to the standards of evidence that apply in the discipline of mathematics. That it “feels right” might be recognized as an intuition and valued as such as a starting point. But it would be appropriate to ask the student to examine this intuition and push for a more mathematically relevant basis for it. There are thus different standards of evidence in different fields, and students need to be inducted into those different kinds of academic communities.’[7]

Or as Shanahan and Shanahan put it

Disciplines differ extensively in their fundamental purposes, specialized genres, symbolic artifacts, traditions of communication, evaluation standards of quality and precision, and use of language.

With regard to language use, different purposes presuppose differences in how individuals in the disciplines structure their discourses, invent and appropriate vocabulary, and make grammatical choices.

Shanahan and Shanahan 2012[8]

Oracy and opinion

Devoting space to enabling the voicing and listening of each other’s opinions is sometimes seen as the pinnacle and main purpose of oracy. Robin Alexander talks about dialogic teaching that ‘extend[s] thinking through ‘collective, reciprocal, supportive, cumulative and purposeful classroom talk.’[9] The whole purpose of this piece however is to argue there is not one purpose for oracy. Rather there are several different purposes – or several different oracies if you will – and being clear about why we are doing what when is crucial if things are to be done well, rather than in a fit of breathless, modish enthusiasm.

Insofar as talk promotes the integrity of the discipline, and genuinely extends thinking without exerting a disproportionate opportunity cost, then it is to be recommended. However, talk can sometimes be eagerly adopted without sufficient understanding of what promoting the integrity of the subject involves.

For example, the role of opinion in history is often misunderstood. Within history, developing student’s ability to voice informed opinions about differing interpretations is an important curricular goal. The National Curriculum for history states that part of the purpose of study is to:

‘…equip pupils to ask perceptive questions, think critically, weigh evidence, sift arguments, and develop perspective and judgement.’

In this concept cartoon from Voice 21, the four fictitious characters voice different reasons, all drawn from historical sources, which contributed to Hitler becoming Chancellor. Crucially, children are not being asked ‘why do you think Hitler became Chancellor?’ They are being asked a question that might initially appear as only slightly different ‘which of these [historically evidenced] causes do you think were most influential in Hitler becoming Chancellor? They are being asked to voice an opinion that is grounded in historical evidence, and how to weigh different pieces of evidence.

Compare this with the example below, also from Voice 21. This asks the children for their opinion about whether or not it was right to evacuate children during World War 2. But this is not a historical question! Here, children are not being asked to make historical judgements. Answers to historical questions must be grounded in historical evidence. Where opinions are discussed and weighed, these should be the differing opinions of those living through events as they happened. The sort of question which looks back at the past from the standpoint of the present and makes judgements about whether or not they did the right or wrong thing is what is called ‘presentism’ and is NOT history! Whether or not Tamana thinks some cities were dangerous is irrelevant, unless Tamana is a citizen in 1939 whose views we have access to. Were this cartoon redrawn to reference differing opinions from people at the time, based on evidence, then it would become an appropriate tool for use in a history classroom.

If opinion giving is valued without understanding the role of knowledge in each subject in informing those opinions, and what kind of opinions are appropriate and inappropriate, then we are stepping into dangerous territory.

The arts, and some aspects of English, are subjects with an expressive quest. Here, the personal responses of others to a piece of work, as well as the ability to articulate an informed personal response oneself, is part of the curriculum. Here, we might say ‘there are no wrong answers’ (though clearly there can be naïve, or ill-informed answers). We might say as a matter of principle, in this context learners have the right to make their own interpretation that may differ from their peers or their teacher. Diversity of thought and absence of consensus are acknowledged and may even be championed. This is quite different from the descriptive quest subjects where there are very definitely wrong answers. Within descriptive quest subjects, the viewpoint of the knower is irrelevant. Single truth is assumed to be possible and desirable. Similarly in interpretive subjects, there are wrong answers. The opinion that the moon landings did not happen is discernibly false, for example. Indeed, subjects with a strong interpretive quest are perhaps most at risk from misunderstanding about opinion, precisely because scholarly opinion does differ and debate between scholars is constitutive of the subject. But unlike the expressive quest, while this diversity of opinion is acknowledged, it isn’t championed in the same way it is within the expressive quest. Access to a single historical truth might be impossible, but historical opinions are bounded by evidence and are not infinitely flexible.

That said, the curricular rationale for exploratory talk in subjects with interpretive and expressive quests is relatively straightforward, and will be focused on developing the ability to provide informed opinion. But this is not to say that exploratory talk does not have a role in descriptive subjects such as maths and the sciences. However, within descriptive subjects, giving one’s opinion is unlikely to be a curricular object. In maths, justifying one’s reasoning with reference to logic or being able to give a proof is an important part of the maths curriculum to which oracy needs to contribute. One of the aims of maths is described in the National Curriculum as developing the ability to

‘…reason mathematically by following a line of enquiry, conjecturing relationships and generalisations, and developing an argument, justification or proof using mathematical language.’

NCETM in their article Four ways to create better mathematical talk in your classroom propose that as well as checking for understanding teachers should create:

‘opportunities to talk about something other than ‘the answer’ can create a more discursive atmosphere and reduce inhibitions by removing the anxiety of being ‘wrong’. For example – classifying, comparing, focusing on method rather than solution. Questions such as ‘What do you notice?’ or ‘What do you think would happen if…?’ can be useful.’

The curricular importance of this is that there is more to maths than finding answers. Being able to think mathematically and communicate that thinking to others is central to what it is to learn maths. This article by Mike Askew is an interesting account of how he does it as well as potential pitfalls.

In science the National Curriculum has a section on spoken language which says

‘The quality and variety of language that pupils hear and speak are key factors in developing their scientific vocabulary and articulating scientific concepts clearly and precisely. They must be assisted in making their thinking clear, both to themselves and others, and teachers should ensure that pupils build secure foundations by using discussion to probe and remedy their misconceptions.’

If we unpick this using the lens of pedagogy and curriculum, we can see that a curricular object includes

- Articulating scientific concepts clearly and precisely

This is clearly not about giving opinions.

Pedagogically teachers are to

- Ensure that pupils build secure foundations by using discussion to probe and remedy their misconceptions.’

This is classic checking for understanding

And then, straddling both the pedagogical and the curricular

- Making thinking clear to themselves and others

Articulating scientific concepts clearly and precisely involves both the pedagogical use of talk as a way of framing and extending initial thoughts and also learning the ways in which specifically scientific discourse uses particular structures. The Ofsted subject review for science said that

‘To learn about science, pupils need to learn about the different ways in which scientists engage in their work: through reading, talking, writing and representing science.This is called disciplinary literacy. It is not the same as teaching generic literacy strategies needed to interpret any text. Instead, it involves pupils learning how individuals within a discipline‘structure their discourses, invent appropriate vocabulary and make grammatical choices’.

This is where talk can be used in the science classroom as a prelude to writing scientifically, developing confidence with the vocabulary and grammar of the subject.

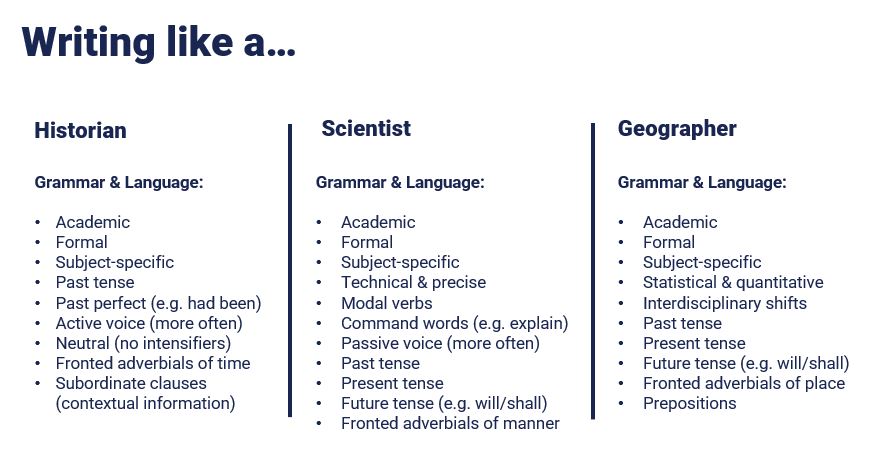

Juli Ryzop of the Knowledge Schools Trust has analysed the different grammatical patterns used in history, geography and science. I strongly recommend her training on this. [10]

Here is a slide from her training:

In order to write like a scientist, or historian and so on, we need to also be able to use disciplinary talk. While this may start out in exploratory mode, the goal is to recast it into formal scientific sentence idiom.

What we need to avoid is the imposition of forms of talk appropriate in one subject into another without regard for the structure and linguistic demands of that subject. We don’t want science teachers to be dragooned into watching English classes giving their opinions about a charged piece of writing and expected to do similar when students are learning about charged particles. We don’t want maths lessons where giving different methods of solving a problem is over-valued to the extent that giving a different method becomes an end in itself rather than a useful way of exploring mathematical thinking.

Curriculum and phase

As well as thinking about how the subject shapes oracy, we also need to consider how the age of the child influences choice of curricular objects.

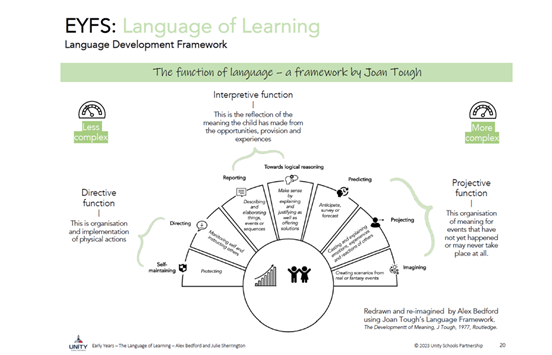

In the Early Years Foundation Stage, communication and language is an area of learning in its own right. Because children are at the earlier stages of learning to communicate, oracy curricular objects predominate. These include not only the cognitive and linguistic aspects of oracy, but also the physical and social and emotional. For example, see this from Alex Bedford and Julie Sherrington’s [11]EYFS: Language of learning

These ways of communicating should then built on in key stage one as children receive a curriculum planned to enable them to develop the ability to

- talk to inform and listen to information

- talk to entertain and listen to entertainment

- talk to discuss and listen to discussion

and then in key stage two deepen all of these in progressively more challenging contexts as well as learning how to

- talk to persuade and listen (critically) to persuasion.

I have written about this in a bit more depth and how they link to different subject areas in the ResearchED Guide to Primary Literacy which is due to be published in October 2024.

In almost all primary schools, the same teacher teaches many subjects to the same children. Because the use of accountable talk requires an investment of time before it is able to be used well, it may be easier to establish in a primary classroom where the same routines and have the same expectations can be applied across several subjects than in a secondary context where one might expect that implementation will be harder and opportunity costs potentially higher.

Some of the strategies from Voice 21, work well across all phases. Others are more appropriate to earlier stages of language development. Learning how to use ‘because’ when talking to give reasons is an appropriate curricular object in the Foundation Stage and year one and crafts readiness for the later use of conjunctions when writing narratives and when reasoning in subject specific ways. Playing a ‘because’ ice breaker in year nine is closing the gate several years after the horse has bolted.[12]

Oracy and assessment

Don’t get bogged down in how to assess oracy. Effective learning is not dependent on being able to quantify it with some sort of data label or being able to ‘provide evidence.’ As always, formative assessment that allows teachers to respond in real time in the classroom is by far and away the best use of assessment. This requires teachers to have a good mental model for what if means to get better at speaking and listening, informed by specific subjects. The mental model is provided by the subject curriculum, not an assessment rubric.

However, having some way of summatively evaluating standards of talk is something that is being explored. For example, Voice 21 have written this on the subject. No More Marking, the comparative judgement experts, have written this. What is interesting here is that progression is given via the complexity of what is talked about, rather than the fools errand of trying to describe progression in skills, which invariably ends in trying to make adverbs discriminate between performances, in an entirely subjective and ultimately meaningless way. Whereas if the curriculum is the progression model, increasing challenge involves the same skill being applied in progressively more challenging contexts. This is why ‘oracy’ curriculums where oracy is hived off from what is being talked about don’t really work for the linguistic and cognitive strands. For example, see this example. Year one are asked to offer reasons for opinions. But it makes a lot of difference to the level of challenge whether you are being asked to give reasons for why you like a playing football or why you think economic reasons were the chief cause of the rise of Hitler. The complexity of the knowledge one is being asked to talk about is what provides the level of challenge. This probably matters less for the physical and social and emotional strands, though even here being asked to read with prosody a page from Dear Zoo is going to be easier than the prologue of Macbeth. Encouraging everyone to contribute is much easier on relatively uncontroversial topics and much more challenging when the subject matter is hotly contested.

In conclusion

- Oracy should contribute to, rather than detract from or be seen as in competition with, knowledge building. If oracy in the classroom isn’t playing a role in building knowledge, then it is likely to be misplaced. [13]

- Building knowledge does not preclude exploring knowledge. Exploring knowledge is sometimes a good strategy for building knowledge. And sometimes not.

- Oracy includes checking for understanding. Closed questions have a valuable pedagogical role in this. Viewpoints that are dismissive of such exchanges as ‘not proper oracy’ should be viewed with scepticism

- Be wary of approaches that either insist that children speak in full sentences all the time, or who conversely do not appreciate the need to be able to talk in full sentences when it is appropriate to do so. Don’t forget to read my blog about this!

- Learning to communicate in sentence-based idiom requires thoughtful scaffolding such as sentence starters and sentence builders. Just getting children to talk about stuff won’t be sufficient.

- Approaches to oracy that reduce it to giving opinions are facile. This is even more the case when the opinions are not grounded in knowledge.

- Be aware of how the knowledge architecture of subjects drives the kind of talk that is appropriate. Discussion and argumentation based on differing opinion is integral to interpretive and expressive subjects. Within descriptive subjects the emphasis is on explaining reasoning.

- Whole school oracy practices need to take into consideration subject and age considerations rather than imposing generic expectations that run roughshod over these.

- Beware assessment. Something is not more or less valuable if it is summatively assessed. There are lots of reasons to teach through or about oracy. Teaching oracy in order to generate evidence is not one of them. That way lies madness.

- Voice 21 have some good resources and some not so good resources. Regardless Listen to other voices such as Doug Lemov and Adaptable Talk as well as Voice 21.

[1] The transformative power of oracy – ORACY CAMBRIDGE

[2] See page 11 of Oracy-across-the-Welsh-curriculum-July-2018.pdf (oracycambridge.org) for a summary of key research findings.

[3] I say at which point in a lesson because sometimes things get misconstrued and what is intended to be a technique used for say 5 minutes within a lesson is understood as being the only technique used at all! As if actual teaching with clear explanation of content could be replaced by non-stop cold calling and talk partner routines!

[4] Alexander, Robin (2020) A Dialogic Teaching Companion. Routledge p15

[5] I’m looking at you ECF framework.

[6] From the University of PittsburghAccountable talk® sourcebook: for classroom conversation that works

[7] From the University of PittsburghAccountable talk® sourcebook: for classroom conversation that works page 6

[8] TLD200095_HR (shanahanonliteracy.com)

[9] Alexander, Robin (2012) Moral Panic, Miracle Cures and Educational Policy: what can we really learn from

international comparison?, Scottish Educational Review 44 (1), 4-21

[10] Juli can be contacted via @juliryzop.bsky.social Her training is equally suitable for secondary and primary practitioners.

[11] EYFS: Language of learning.

[12] Though clearly may be appropriate for children with moderate or severe learning difficulties or for children learning to communicate in a language that is very new to them.

[13] I’ve talked of the role of oracy is building belonging. One can build belonging while building knowledge. these two are not in competition.