Another weekend, another Twitterstorm. The Policy Exchange have just released a paper arguing for more availability of ‘coherent curriculum programmes’ which include, among other things, lesson plans, text books and lesson resources such as worksheets. Unfortunately the TES reported this as ‘The solution to the workload crisis? Stop teachers designing their own lessons’ which, understandably, has gone down like a bucket of cold sick on Twitter. The fear being that this augers the triumph of the neo-liberal take-over of education, with lesson plans direct from Pearson delivered straight to the classroom by Amazon drone. Or, to refer to my possibly obscure title, delivered by motorbike by Just Eat, with the teacher’s role limited to opening the plastic cartons and serving them out; lamb bhuna tonight, whether you want it or not.

Having read the entire article, what the article is actually proposing is something much more reasonable: debatable, but reasonable. The argument goes that the 2014 National Curriculum is not being implemented as well as it possibly could because the appropriate resources and training to implement it well either don’t exist, or if they do exist, are hard to locate among the myriad of online resources. It bemoans the current situation where many teachers trawl through online resources, of possibly dubious quality, late into the night, as they attempt to plan each and every lesson ‘from scratch,’ although in reality, probably ‘from Twinkl.’[1] This is wrong, the report argues, because the ‘lesson by lesson’ approach is highly unlikely to result in a coherent curriculum that hangs together across the year groups, or that provides sufficient provision for revisiting previous learning. The workload argument is more of a side issue in the report, not its main thrust. Its main thrust is about having a coherent curriculum.

I’m all in favour of coherent curriculum. Indeed, in this blog I argue for curriculum design that has coherence not only within each specific subject, but across subjects. Yet the type of ‘3D’ curriculum I’m advocating is extremely time consuming to write. We’ve been at it for almost 2 years and it’s not where I want it to be yet. The same situation is being replicated across the country. In my ideal world, the DfE would pay me and my selected Twitter mates to devote ourselves to this task, but since (doubtless due to unintended oversight) the report fails to mention me explicitly by name, it comes up with the suggestion that the Government should have a curriculum fund that brings ‘teachers with curriculum planning ideas together with institutions who can provide quality assurance and wider scale distribution.’p36 The kind of institutions it posits as being in a position to do this are multi-academy trusts, learned societies, subject associations and museums. What about schools not in MAT’s, I’d argue? As otherwise that means the vast majority of primary schools would be overlooked, and surely some of us have something to offer? And what about the BBC?

So, while I might argue with the detail about who might and might not secure funding to write detailed, coherent curriculum programmes, I think this is an excellent idea. I’d much rather use a curriculum resource written by a bunch of teachers in partnership with, say, a museum than by most educational publishers. Especially if there existed a range of quality assured, kite marked resources that schools could choose to use, if they wanted to. Many primary schools already use ‘off the peg’ curriculum packages, usually for discrete subjects but occasionally across the curriculum. [2] What is lacking is the all-important question of quality assurance. At the moment, schools buy in all sorts of ready-made packages for aspects of their curriculum. With Ofsted signalling its intention to scrutinise the quality of the curriculum (which in a primary school context is shorthand for ‘everything other than English and maths’), primary headteachers are tearing their hair out trying to rustle up a coherent curriculum offer for the foundation subjects while secondary heads fret about ks3. Just off the top of my head, I can think of the following resources that primary schools of my acquaintance use.[3] Jolly Phonics, Third Space Learning, Cornerstones Curriculum, White Rose, Literacy Shed Plus, International Primary Curriculum, Developing Experts, Jigsaw PHSE, Discovery RE Val Sabin PE, Rigolo, Discovery Education Coding, ReadWriteInc, Maths Mastery, Charanga.

The thing that strikes me going through this list is that there are lots of different resources out there for maths and phonics and plenty for those really specialist areas of the primary curriculum where many primary teachers are more than willing to ‘fess up to having little to no subject knowledge and welcome explicit handholding; PE, music, computing. But for geography and history, I know of nothing except for Cornerstones and IPC, which offer many subjects. I think it is fair to say to both parties that the IPC is not quite what the authors of the 2014 National Curriculum quite had in mind. And neither of these curriculum packages have the sort of horizontal, vertical and diagonal links that I would argue an excellent curriculum should be striving to build within and across subjects.

However, I really do understand the horror some teachers are expressing on Twitter today about having the planning of lessons taken away from them. The two main objections are that no ‘off the peg’ lesson can ever hope to meet the specific learning needs of the diverse classes we all teach and that planning lessons specifically for one’s children was one of the best bits of teaching, part of what made the job rewarding.

So, finally, let’s get back to the title. In the report, the author John Blake suggests that coherent curricular programmes could be thought of as ‘oven-ready’ – presumably a sort of educational ready meal that just needs a bit of warming up. He argues that these would be especially useful for teachers new to the profession or new to a particular subject. And to be honest, even those of us who love lesson planning probably don’t mind using ‘ready meals’ for some subjects where they lack subject knowledge. If you told most primary school teachers that they were not allowed to use externally produced resources for computing, MFL or music, for example, and had to plan every lesson entirely from scratch, then there would be tears. (Except for the highly knowledgeable minority, of course, who might not understand what all the fuss was about).

Blake then goes on to talk about ‘the final foot.’ What he means here is how teachers could take an ‘oven ready’ resource and then use their professional expertise to adapt it as necessary for the realities of their class. Much of the groundwork having already been done, the teacher is freed up to tweak the lesson to fit their children. This is what I meant by the ‘Hello Fresh’ approach. Hello Fresh is one of those companies that delivers boxes of food with all the ingredients you need to make the particular recipes it also provides. Everything is already in exactly the right quantity, all the cook needs to do is chop, peel, and actually cook the ingredients. Unlike a ready meal, this gives you scope either to follow the recipe slavishly, or, for those who feel confident, add or omit ingredients according to your family’s preferences, play about with cooking times (because you know your cooker best, right) or even go completely rogue and use the ingredients in a completely different recipe, maybe adding in other ingredients bought elsewhere and chucking others.

Yet I understand that some teachers will still object and see this as an assault on their professional autonomy and creativity. When I was a class teacher, I loved lesson planning. So it was with some trepidation that 4 years ago we tried out a particular maths scheme that has very detailed, partially scripted lesson plans. I’m not going to say which one because I’m not specifically arguing for the merits of that particular programme or not, but about the idea of using very detailed plans written by others. (Besides which, many of you will either already know or be able to guess). Anyway, we got funding with one class. The class teacher was happy to give it a go, though she was already an experienced, skilled teacher. The reason why she soon loved it was because it wasn’t a ready meal, it was more of a ‘Hello Fresh’ kind of thing. In fact, you had to tweak the lessons because, as the programme makes quite clear, they are aimed towards the average child and your actual children aren’t average. Some will need more challenge, more depth, others will need more support. So the teacher needed to think about how to adapt every lesson for the particulars of their class. The teacher also needed to decide whether or not to spend more time on a particular lesson, skip over lessons if the class didn’t need them, swap suggested manipulatives for something else, and had the freedom to design their own worksheets or to not use any worksheets at all.

What made this possible was that the programme wasn’t really a set of resources, it was a training programme, of which resources were a part. Each unit of work included a video explaining key concepts, an overview, links to articles and research, as well as the lesson plans and flipchart slides to go with it. These resources are excellent and go far beyond what any of us in school would have been able to offer. And ours is a school unusually blessed with knowledgeable maths teachers. There was also some central training and the expectation that the maths leader was regularly coaching teachers new to the programme. Indeed, during the first year, our maths leader, a year 6 teacher, had to teach year 1 maths once a week using the programme, so that she became familiar with it. Without this training, the resource would not have had half the impact it did.

Now you may argue, if you had to do all that tweaking, what on earth is the point? You might as well have designed the whole thing yourself. Well no, even with the tweaking, lesson planning was much quicker. But why our first teacher really loved it, and why the subsequent teachers to use it also love it, is because it is so clever. The progression and the way it comes back to topics again and again, the way it builds in reasoning at every step, the way it moves children away from reliance on counting and towards reasoning based on known facts is excellent. We might rate ourselves as excellent maths teachers who can plan fantastic lessons, but we simply do not have the expertise or time to develop a scheme of such quality. What really struck me doing lesson observations one week was how brilliantly progression is planned into the scheme. I saw addition lessons in year 1, 3 and 4 and in each lesson exactly the same structure was used, but with increasing complexity. Given its obvious superiority to anything we could produce, it would be foolish and arrogant to insist that we had the ‘freedom’ to plan our own lessons, just because we liked it. Nor do teachers feel reduced to mere delivery bots. I really feared they might, but that just didn’t happen. Because the lessons made sense. And where, very occasionally, a lesson didn’t seem to work, they had the freedom to teach it again, their way.

That’s not to say we don’t occasionally do things differently. For example, I think this way of teaching telling the time is better, so we don’t use all of their resources for that – just some. And we are encouraged to comment on lessons and suggest improvements which are listened to. Because the resource is online, rather than a textbook, when they adapt the programme, we don’t have to throw out costly resources. Were there to be similar quality programmes in other areas of the curriculum, I would buy them like a shot.

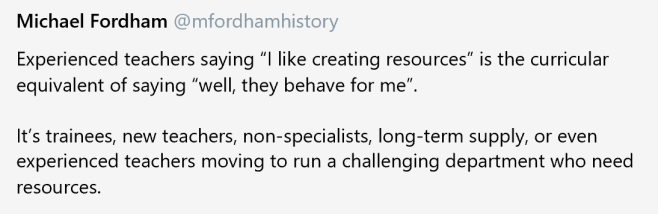

However, I also really understand that many teaches love the creativity that planning affords and would be loath to relinquish it. On the other hand, just because you love doing something, doesn’t mean everybody does. As Michael Fordham says:

Instead, as an alternative to moving into leadership, more experienced teachers should have the option to move into curriculum design themselves. This is what happens in Singapore, where experienced teachers have options to move into senior specialist roles that work on areas such as curriculum design, testing, educational research or educational psychology.

With talk here of sabbaticals for teachers, maybe one sabbatical opportunity could be to work within a curriculum development team, producing resources for others to use?

[1] The report doesn’t mention Twinkl, that’s me, being facetious.

[2] I can only comment in detail on primary schools. Maybe it’s different in secondary schools where teachers are subject specialists? But from talking to many secondary teachers, I don’t think it is as different as all that.

[3] Inclusion in this list does not mean I think the resource is either good or bad. We use some of these; some I wouldn’t touch with a bargepole.

I think I know the maths scheme of which you write – and yes, I kind of liked it (apart from the fact it didn’t cover anything), and yes, when it’s run properly it allows teachers freedom to adapt. The thing that popped into my head, though, was the QCA units. Is there a danger we will go back to that, I wonder?

LikeLike

QCA wasn’t great, and there is always the danger that once something is printed, bound and official looking, it is perceived as holy writ and imbued with an authority far beyond that which it claims itself.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes. And that you can’t move away from it or innovate for what is appropriate for your circumstances.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] a measured and informative analysis of this issue, Clare Sealy’s blog is a must read, and I don’t propose to tread the same ground in this piece. What I’m aiming to […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

Hi Claire enjoyed your piece linked to the Policy Exchange report – you’ve mentioned relative lack of resources for geography and you and colleagues might be interested in the geography resources we’ve produced. There’s a series of units linked to the National Curriculum with a wide range of additional A/V, interactives, maps and other support. All are freely available via http://www.rgs.org/schools – just click through to the resources section and use the search to narrow down to primary.

Hope you find it useful

best wishes

Steve

Steve Brace

Head of Education

Royal Geographical Society

LikeLike