It seems like a life time ago but this time last week I should have been at ResearchEd, listening to great speakers and getting butterflies about my session later that day. Except that I slipped on the hardboard down on the kitchen floor courtesy of our kitchen refit and ended up in A&E instead. Luckily nothing is broken and my leg is slowly getting better. I’m so sorry I couldn’t be there.

A few people asked if I could put my slides up. The problem was I had taken Oliver Caviglioli’s work on dual coding very much to heart and knew that written text and spoken text delivered together can overwhelm the working memory whereas the brain deals much better with spoken text alongside images. My slides where therefore 99% word-free but image rich, the intention being that I would explain the slides verbally without recourse slides full of bullet points. What I was going to say was in my head rather than written down. The trouble being that without some sort of narration, the slides are hard to make sense of. So what follows is a a blog based on what I would have said, though probably a bit longer than the 40 minute slot would have afforded. I’ve used many of Oliver’s excellent graphics in my slides.

Does the best learning result from memorable experiences?

Children tend to easily remember exciting things such as plays and trips. This leads some teachers to suggest that the key to getting children to remember things is to make lessons full of exciting, memorable experiences. While not an unreasonable supposition, it is based on a misconception about how remembering works. The misconception arises because most teachers are unaware of the difference between semantic and episodic memory.

Episodic memory is where we store the ‘episodes’ of our life, the narrative of our days. This is the autobiographical part of our memory that remembers the times, places and emotions that occur during events and experiences. We don’t have to work hard or particularly concentrate to acquire episodic memories, they just happen whether we like it or not. When we talk about having fond memories or an event being memorable, we are talking about episodic memory. We are talking about something that happened, something where details of time, place and how we felt at the time are central.

Semantic memory is where we store information, facts, concepts. These are stored ‘context-free’, that is, without the emotional and spatial/temporal context in which they were first acquired. These type of memories take effort, we have to work to make them happen. In fact, we don’t tend to use the word ‘memories’ for this kind of stuff, we tend to use the word ‘memorise’. After all, we don’t say ‘I have memories of the 7 x table’ we say ‘I have memorised the 7 x table.’

Episodic memory is, at first glance, the more ‘human’ of the two, the memory of people, feelings and places that makes us who we are. Semantic memory seems colder, more robotic. More Mr Spock than Dr McCoy. Yet it is our amazing ability to store culturally acquired learning in our semantic memory that makes as so successful as a species. The key purpose of education is to build strong semantic memory, to pass on the knowledge built up over centuries to the next generation; how to read and write, how stories work, how to use mathematical reasoning to solve problems, science with its amazing power to gives us to predict the future and the myriad of other concepts, ideas and practices. That is not to say that building semantic memory is the only purpose of education. We want to help form children who are emotionally literate and morally responsible too, and that will involve thinking about the kind of episodic memories we try and build for our children. If we treat our children with kindness and respect, they will have episodic memories of what it was like to be treated kindly and respectfully, which makes it more likely they too will treat others with kindness and respect themselves. Nor is it to say that there should be no consideration of creating the kind of memorable experiences that trips and plays and so forth afford. Such special events that punctuate the day to day routine of school life are the festivals, the ‘Christmas dinner’ of the school year. They are special because they are infrequent and resource-heavy and different. They contrast with the every day, bread and butter hum drum familiarity of ordinary school life. But the every day is our core purpose.

Episodic memories may be acquired effortlessly, but they come with several drawbacks in terms of acquiring skills and knowledge.

Episodic memories come tagged with context. In the episodic memory, the sensory data – what a child saw, heard and possibly smelt during a lesson – alongside their emotions, become part of the learning. These emotional and sensory cues are triggered when we try and retrieve an episodic memory. The problem being that sometimes they remember the contextual tags but not the actual learning.

I’m sure we’ve all had those lessons when children remember all about the colour pens they were using or that we used post its or that Miss spilled her coffee but that actual content of the lesson itself? That’s gone!

Episodic memory is so tied up with context it is no good for remembering things once that context is no longer present. Luckily our brains also have semantic memory. Semantic memories have been liberated from the emotional and spatial/temporal context in which they were first acquired. And once a concept has been stored in the semantic memory, then it is more flexible and transferable between different contexts.

Think about your own learning at school. To be sure you will have some episodic memories of what you actually learnt, but for the most part, the episodic context-dependent aspects have long since faded. What endures is semantic memory that you won’t remember actually learning because the ‘memorable’ context has long been forgotten, episodic brass traded for semantic gold. In this list below, see if you actually recall learning any of this stuff. Probably not, yet you know it (or most of it) and though maybe you have not thought about ox bow lakes for decades, at the very mention, back the memory comes, effortlessly. That’s the beauty of semantic memory . It isn’t, and doesn’t need to be, tied up with episodic clutter. We don’t need to have fond memories of sitting on the carpet in Reception whilst Mrs Blackburn told us all about triangles to know about triangles.

Semantic memory is context free.

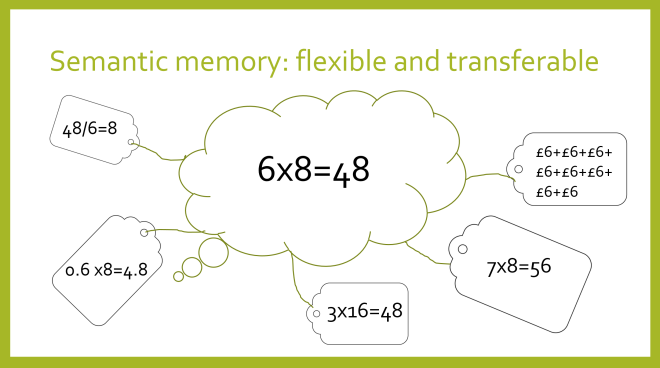

Because they are context free, semantic memories are much more flexible and transferable than episodic memories.

So they are much more useful. Semantic memory is what we use when we are problem solving or being creative because both of these involve applying something learnt in one context to another, novel context. Episodic memories by contrast aren’t flexible and don’t easily transfer because they are anchored in specifics.

Since enabling problem solving and creativity is the ultimate goal of education, it is crucial that teachers have very good understanding of how to ensure that what we teach them stays learnt, that what we impart makes that all important journey from the episodic to the semantic memory. Yet few teachers have had any training on this. What is more, once you start to understand the learning journey, you realise that much of what schools focus on only addresses half (if that) of the learning journey. Our teaching and learning policies and the centrality of lesson observations as levers for school improvement tend to focus on individual lessons, whereas if we know about how semantic memories are formed, we will realise that a lesson is the wrong unit of time as Bodil Iskasen wrote. (The link to her seminal blog on this does not seem to be working so I’ve linked to David Didau writing about her idea.)

To understand this, we need to understand about how we come to remember stuff. I’ve written about this here and the following slides also remind us of the process. If you are already all Willingham-ed up, you might want to skip this bit.

When we teach something, the information goes first into the working memory and then, in the right conditions, it passes into the long term memory. Once here, memories can be retrieved back into the short term memory when we want to think about that particular thing. Hence, although I have not thought about ox bow lakes very much for 30 years, I can remember what they are, after all this time. However, as we all are only too aware, the process does not happen quite as straightforwardly as we would like. We teach stuff, yet our students seems to undergo a mysterious mind wipe, sometimes within hours. Stuff gets forgotten.

Our teaching and learning policies, our cpd and our lesson observations are all focused on the initial learning part of this journey. They pay no heed at all to the second leg; the bit where we remember, or don’t remember stuff beyond the narrow confines of a single lesson. So sometimes we are baffled when seemingly great teachers get not so great results. Or possibly vice versa. that’s because we’ve only looked at part of what it takes to learn something in the long term. We’ve only looked at this.

Or maybe even just this

In other words, we’ve neglected the part of the journey that happens subsequent to the information arriving in the working memory, the stuff that makes knowledge actually stick around long term – an egregious oversight with all too familiar consequences.

Whereas we should also focus on this.

Since lesson observation only focuses on the here and now of a lesson at the point of delivery, it is of limited use in helping see if learning is actually happening. Learning is a long-term process, yet we try and ‘see’ the unseeable by looking at proxies, all of which tell us very little about whether learning is beginning to happen or not, as Robert Coe explains here.

Teaching for long-term learning

If we want to maximise long-term learning, we need to be aware of the three pressure points where our learning may go awry. Traditionally, we have focused on the first of these points and not paid any attention to points two or three.

The working memory is has very limited capacity and is easily overwhelmed. By contrast, the capacity of the long term memory is vast. If we want children to remember stuff for the long term, we need to make the most of this huge capacity. The aim of all learning should be to improve long term learning.

The first hurdle, the one we are most familiar with already, is to make sure that what we teach actually makes it to the working memory in the first place.

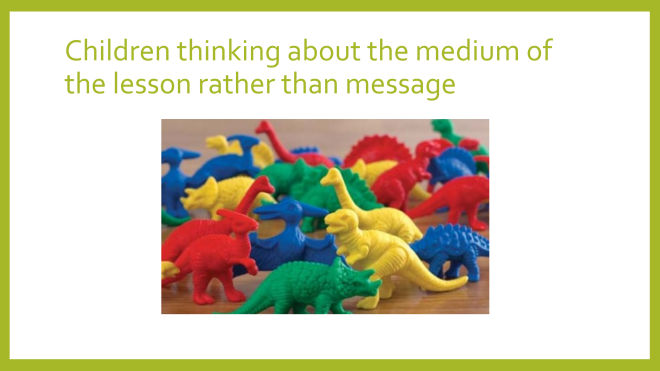

We remember what we think about, so lessons need to be planned so children think about the right things. If they are thinking hard about what colour pen to use in their poster or how they might win a game, rather than what the poster is about or the maths behind the game, then that’s what they will remember.

This can be a danger with exciting ‘memorable’ lessons. The exciting but extraneous features are what get remembered, rather than the more prosaic, but more important information that we want them to learn.

For example, when teaching young children to count, sometimes using ‘interesting’ objects means the child’s focus is more on the dinosaurs than the counting. So that’s what gets remembered.

Of course the converse is also true. If a lesson is so tedious that all anyone can think about is how boring it is, then that will be what is remembered, at the expense of content.

The second hurdle to be cleared is making sure that the information in the working memory makes it to the long term memory, without leaking out. As Peps McCrea writes in ‘Memorable Teaching’

Our WM is a high maintenance mechanism. Give it too little to play with and it begins to look for more interesting fodder. Give it to much to juggle and it’ll drop all the balls.’

This is the basis of Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory.

Cognitive overload occurs when we overwhelm the limited working memory with too much new information at once. Since most of us can only handle about 4 new items of information at once, stuff will start to leak if we try and put too much in at once.

We can avoid cognitive load by breaking stuff down into small steps. Unfortunately the ‘curse of knowledge’ makes us forget quite how complicated certain concepts are. See this series of excellent blogs by Kristopher Boulton where he explores breaking down the concept of simultaneous equations into tiny steps to make sure no-one gets lost along the way.

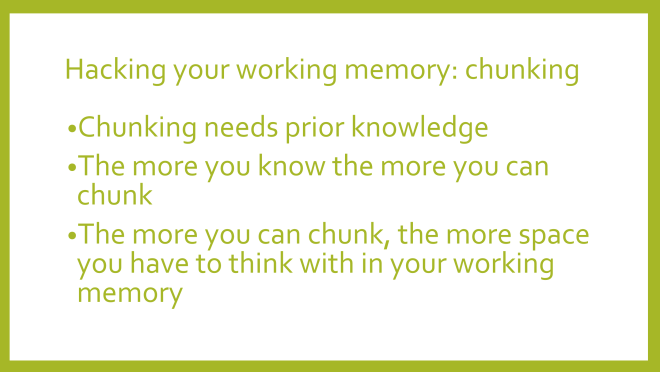

Fortunately, we can ‘hack’ the limits of our working memory. Our brains like to connect together related ideas into chunks. The great news about this our working memory then regards the big ‘chunk’ as one item, occupying one slot.

So for example, when children begin to learn to read, each individual letter had to be decoded, so reading is slow and hard work. If the text is too demanding, the child cannot attend to the meaning of the text at the same time. Later, the child can decode more fluently because through practice, phoneme-grapheme correspondences have formed a great big chunk called ‘reading’ and getting words of the page takes up very little working memory. The child’s working memory is now fully available to think about what they are reading, rather than thinking about what the words say. Having secure recall of number bonds and times tables helps students in a similar way have the brain space to think about the new maths they are learning. How many times have children failed to understand vertical addition, for example, because so much brain power is going into adding two 1-digit numbers together that all that stuff about columns and place value you are trying to impart falls by the wayside. When students go to secondary school and learn about the Norman Conquest, they will do so much more easily if the concept of invasion already has some flesh on its bones because they already know about Viking and Roman invasions and World War 2. Invasion, resistance, conquest and defeat will already be chunked together and understood.

Having a rich store of knowledge available in one’s long term memory ready to be drawn upon by the working memory is therefore crucial.

This is why having lots of rich knowledge is so important. The limitations of the working memory can be bypassed by using the resources of the long term memory. Those with limited knowledge are unable to do this, so are much more likely to experience cognitive overload.

This has big implications for our curriculum design. If we want successful learners, instead of over focusing on the quality of teaching, we need to pay attention to the quality of what gets taught. Is it suitably knowledge-rich? If instead we focus too much on giving children fun-filled ‘memorable’ experiences, we are depriving them the vital ‘nutrients’ they will need later. It’s equivalent to feeding children on happy meals rather than balanced, nutritious meals. That’s not to say children should never have ‘fun lessons’ at school, anymore than children should never eat junk food or birthday cakes or sweets.

The third and final hurdle is all about retrieval. Knowledge might have got into to our long term memory, but how easily can we find it?

You know that exasperating feeling when you know you know something but you just can’t remember it right now? Or you remember (episodically) that you did know something, but can’t bring that thing to mind when you need it. That’s a bit like when you’ve saved something on the staff drive but didn’t name it properly, let alone put it in a folder where you might stand the faintest chance of relocating it again. Not that that sort of things happens at St Matthias. Oh deary me no.

Let’s hope ‘Doc 6’ wasn’t anything important.

Fortunately, we can do something about this. (About long-term learning that is. The staff drive is beyond help, I fear). We can strengthen our ability to recall long-term memories by retrieving them. The more you search for a memory, the easier it becomes to find it. This simple concept – the retrieval effect’ – should become the bedrock of our teaching for long term learning.

Unfortunately this effect is also known as the ‘testing effect’ which puts some teachers off and confuses others – myself included until recently – so that we see this as an assessment tool. It is not an assessment tool, it is a learning tool. I fear my previous blogs on knowledge organisers might have reinforced that misunderstanding. You might get some assessment data as a by product from some retrieval practice but that is not its prime purpose. Its prime purpose is to make memories stronger.

When we struggle to remember something, this primes our brain to remember it more easily the next time we look. The brain gets the message that this memory must be important because we are looking for it. The more times we try and retrieve something, the stronger the memory gets. But it is the struggle that is important. If we reteach content instead of getting children to try and retrieve stuff they’ve probably forgotten, the memory does not get strengthened in the same way. It seems kinder but actually does the children no favours. We need to explain this to them and help them understand that struggling to remember something is good – it means their memory is getting stronger.

Some children will fail in their attempt at retrieval. That’s fine. Once they’ve struggled, then you reteach.

One way of helping deal emotionally with the stress of not knowing something is by calling retrieval a game of hide and seek. That pesky knowledge is trying to hide from you, but you are going to try really hard to track it down.

And this is what you can say to children who can’t remember!

And then reteach, to help them get better at finding, next time.

The retrieval effect is stronger if we allow a bit of forgetting to happen before getting children to retrieve. Using our hide and seek analogy, if you only count to 5 before you go and ‘seek’, your friends will be pretty easy to find but your ‘seeking skills’ won’t have had much of a work out. Count to 50 and your friends will be well hidden and you will have to work hard to find them. It’s the same with memory. Our memories get stronger once retrieved if we have had time to forget them – bizarre as that sounds.

This is one limitation of some AfL techniques. If we assess whether children can remember something at the end of a lesson before they have had a chance to forget it then while we get get useful feedback about if they understand something or not – and I’m not knocking that – obviously that’s very important to know – what exit tickets, plenaries and the like can’t tell us is if this new learning will be remembered long term (or even tomorrow). Afl techniques can tell us about what has been understood, but to know what has been remembered we need something different, we need assessment for long term learning.

Having retrieval tasks at the start of lessons, be they ‘do now’ tasks, entry tickets, start of lesson plenaries or any other retrieval tasks are more likely to strengthen the learning from the previous lesson than and end of lesson retrieval task.

What is more, to make memories really strong, come back to them at gradually increasing intervals. This is known as ‘spaced learning.’

At St Matthias, one way we do this is by giving children multiple choice quizzes weekly during a 3 week block (in humanities or science) and then by giving them another quiz about 6 weeks later when they are deep in the middle of a completely different block. And then at the end of the year (after a period of revision time when they can self-quiz using their knowledge organisers), giving them a final quiz that covers all the areas of learning in that subject that year. This final end of year quiz does have an assessment purpose too, but it will also provide further retrieval practice and help the knowledge learned that year endure in the long term.

Here’s a year 6 example

And here’s one from year 2.

Another way of maximising the benefit of retrieval practice is by mixing up the content of what you are asking children to retrieve. For example, giving children a fractions question from a unit you did a month ago in the middle of a unit on perimeter.

I stress, this is the pattern for retrieval practice, and not for the initial teaching of concepts.

We use ‘check its’, an idea we got from the Primary Advantage Federation. These are short questions from an area that has been taught at least three weeks previously, without any reteaching of the concept beforehand. For example:

Again, while you could see these as primarily being about assessing what has been retained, we should also remember that as well as helping check what might need reteaching, it also strengthens the memory of what has previously been learned.

Time spent retrieving previous learning is self evidently time not spent learning new stuff. But ploughing ahead with the new without devoting quality time to remembering the old is a false economy. The curriculum is not so much stuff to be covered, it is knowledge for long haul learning. It will pay off in the long term, with less frantic time as high stakes statutory tests approach. And anyway, the pay off should be for the learner who now has a rich store of knowledge in their long term memory rather than for schools grasping after the badges and stickers of high exam honours, as Amanda Spielman reminds us.

Very useful. Very much enjoyed the analogies as they make the theory more accessible: that’s the rich knowledge coming into play. Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting stuff, but …

At primary school (1960s), I remember clearly the moment when I realised I could ‘do’ multiplication. It was when I noticed that if I started from 7×8=56 I could work out most of the rest of the ‘hard’ multiplications.

I also remember, from around the same age, when doing a project on Ancient Egypt, that the story of Egypt began with the unification of north and south, represented so beautifully in the combined crown of the pharaohs.

Both those memories are specific and very contextual but also clearly semantic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes we will all have some memories where the episodic stuff is still there. Maybe there was a particularly strong emotion associated with it- pride perhaps- that made it stick. But most of what we learn semantically isn’t like that.

LikeLike

Is it not possible that the biggest breakthrough moments in our understanding remain associated with context, while our memory discards the context of the less significant moments of understanding simply because we cannot afford to carry all those memories around with us? As another example, I learned Egyptian Arabic to a fairly high standard – I remember well the contexts of the times of breakthrough and insight that moved my understanding forwards, to do with fundamentals of syntax and of rhythm/stress. Obviously I don’t remember all the moments of knowing what the thousands of individual lexical items meant.

LikeLike

Yes though it is strange and unpredictable what we do and don’t remember episodically. Emotion definitely a factor though

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning Πηγή: https://primarytimery.com […]

LikeLike

I know the last word says diagrams and I think the first says theories??

LikeLike

“I stress, this is the pattern for retrieval practice, and not for the initial teaching of concepts.”

Can you elaborate on why you stressed this?

Thanks.

LikeLike

I may be wrong but I think the research is about practising what you have already learnt not new stuff. Haven’t read anything about interleaving and spacing initial teaching

LikeLike

I believe that you are right about the research.

I am interested (especially in maths) to find out whether teaching a lesson and then spacing/interleaving before teaching the next one on the same topic you could get a retrieval effect too. At the end of a lesson the students might have practised a small step/aspect of a topic which can be retrieved at the start of future sessions. In a way, regular teaching timetable is spaced: in Maths the space is initially a day. By teaching a sequence of lessons which gradually increases the space between each lessons you could build retrieval practice into initial lessons too? (You can interleave new topics in the spaces left.)

I am unsure, but if learnt something slowly over a longer period, it might reduce the reliance on the context in which it was learned.

Then it might have benefit in forcing teachers to really think about what is achievable in one lesson – small steps would become more necessary.

I don’t know…

LikeLike

There is a primary maths programme called maths making sense where they do a different topic each day- not sure if that helps or not.

LikeLike

An absolutely brilliant read. Insightful and incredibly useful. Proud that our work on check its: http://www.primaryadvantage.co.uk/prove-its

features in this article. Loving the challenge you have posed us that this is a learning tool and not an assessment tool. Couldn’t agree more. Excited about the potential this article has to support our schools in ‘making memories stronger’. Thank you Clare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Checks its are such a great idea – thanks for sharing them with us. But yes, dawned recently they are a learning tool, not just for assessment.

LikeLike

[…] Here is a very good long-read by Clare Sealy covering all of the basics of cognitive science […]

LikeLike

[…] staff meeting we were discussing Clare Sealy’s @ClareSealy excellent blog post on memory https://primarytimery.com/2017/09/16/memory-not-memories-teaching-for-long-term-learning/ along with Dylan Wiliam’s (@dylanwiliam) TES podcast last week. This post is an attempt to […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really enjoyed your descriptive writing and modelling of brain function. I did neurobiology before going into teaching… still applying my knowledge!!! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just love this article and your descriptions of memory! Vital that teachers have this knowledge to assist learners- particularly those learners who struggle the most!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] school?’, Daisy Christodoulou’s ‘Making good progress?’, the Learning Scientists blog and Clare Sealy’s recent blog about teaching for long term memory. How would I incorporate these approaches into my own teaching […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Episodic and semantic memory […]

LikeLike

Fantastic post. Thank you. I wish everyone interested in Ed. would read it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

[…] my previous blog I explained about how memory works, and how teachers can use strategies from cognitive science such […]

LikeLike

I will take this article to a staff-meeting, and reflect around how we teach for long time learning. Great article, love all the pictures and that it is easy to understand and read. Thank you so much for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] events) rather than sematic memory (memory of facts, ideas, meaning and concepts) (see this blog for more […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning […]

LikeLike

[…] is that if you plan to have lasting, domain-specific outcomes from such a lesson it will likely fall short. A student will struggle to remember any domain specific facts from this method of teaching as the […]

LikeLike

[…] related reading: The section on Cognitive Load Theory in this post by Clare […]

LikeLike

Excellent article – reinforces my gut instinct from years of teaching experience, versus the new wave to push teachers to be entertainers and performers and for students to never be ‘bored’ and excite all their sensory inputs. A paradox for me is that students nowadays have far more access to educational material, videos and all, than us older folks ever did – yet, we see comparative decline in the understanding and analytical skills. Couldn’t agree more that tests are learning tools! Maybe modern media causes cognitive overload compared to the old “chalk and talk” where students actually physically wrote notes (which I believe had merit – had to pass through the brain!!) ?

LikeLike

Fascinating read – thank you! Just finished reading the latest issue of Impact and this has brought that new learning together for me. I can feel my long term memory strengthening through connection!

LikeLike

[…] numerous blogs from Michael Fordham (Knowledge and curriculum – Clio et cetera), Clare Sealy (Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning – primarytimerydotcom) or Christine Counsell: the dignity of the […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] numerous blogs from Michael Fordham (Knowledge and curriculum – Clio et cetera), Clare Sealy (Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning – primarytimerydotcom) or Christine Counsell: the dignity of the […]

LikeLike

[…] What is a knowledge-… on Memory not memories – te… […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on THE CHA WEEKLY READER and commented:

An excellent post distinguishing episodic and semantic memory i.e. the difference between remembering the ‘lesson’ and remembering the intended learning; and progressing to give accounts and examples of effective teaching for long-term retention.

LikeLike

[…] @claresealy blogs about Primary Education with rigour. You can check out here brilliant work here! […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] run the risk of remembering the excitement, rather than the learning. I’ve written before about the difference between episodic and semantic memory. Let me recap the essential differences between the […]

LikeLike

[…] If you are considering your curriculum, you are likely questioning if your curriculum is ‘knowledge rich’, a phrase that has become almost ubiquitous, and on which interesting perspectives abound (eg, from brilliant bloggers Tom Sherrington and Clare Sealy). […]

LikeLike

[…] Rebecca Allen has also argued that much of the progress data collected by schools is unreliable and shouldn’t be used to measure pupil progress. Christine Counsell took up the challenge of measuring progression, arguing that the curriculum should be the progression model. Others have taken up this theme, with Mary Myatt writing on ‘Curriculum – Gallimaufry to Coherence’ and Clare Sealy arguing for a knowledge rich curriculum. […]

LikeLike

[…] If you are considering your curriculum, you are likely questioning if your curriculum is ‘knowledge rich’, a phrase that has become almost ubiquitous, and on which interesting perspectives abound (eg, from brilliant bloggers Tom Sherrington and Clare Sealy). […]

LikeLike

[…] Sealy, C. (2017) https://primarytimery.com/2017/09/16/memory-not-memories-teaching-for-long-term-learning/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning […]

LikeLike

[…] Sunday 5 May – Clare Sealy – Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning […]

LikeLike

[…] Clare Sealy beautifully articulates the central ‘drawback’ of episodic memory here, that the contextual tags are often remembered without the semantic, desired learning, and that […]

LikeLike

[…] Clare Sealy beautifully articulates the central ‘drawbacks’ of episodic memory here, that the contextual tags are often undesirably remembered without the semantic desired content, […]

LikeLike

[…] on just the highlights, including how to construct an effective stem and effective options. Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning. It seems like a life time ago but this time last week I should have been at ResearchEd, listening […]

LikeLike

Excellent information on long term memory and working memory.

LikeLike

[…] Clare Sealy. Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning. […]

LikeLike

could do a trainng like a course

LikeLike

[…] https://primarytimery.com/2017/09/16/memory-not-memories-teaching-for-long-term-learning […]

LikeLike

An absolutely brilliant read! Absolutely phenomenal!!!

Thank you, I’d love to read more

LikeLike

[…] Clare Sealey, Memory not memories – teaching for long term learning. https://primarytimery.com/2017/09/16/memory-not-memories-teaching-for-long-term-learning/ […]

LikeLike

[…] not necessarily the content they were learning. Clare Sealy has written a brilliant post on this here which explores these ideas in much more detail (and probably with more expertise than I do […]

LikeLike

[…] Sealy’s blog, Memory, not memories, is another excellent read on this point of teaching for long term […]

LikeLike

[…] Clare Sealy’s blog ‘Memory not Memories’: https://primarytimery.com/2017/09/16/memory-not-memories-teaching-for-long-term-learning/ […]

LikeLike

[…] just encourages the listeners to read the blog post. He also mentioned in passing Clare’s Memory not Memories post […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

This has been an incredibly wonderful article. Many thanks for supplying this info.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve learn a few good stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how a lot effort you put to create this type of great informative site.

LikeLike